part 1: the spiti trilogy: kinnaur, the verdant side of life and himachal

Sangla valley—Sangla means ‘Pass of Light’ in Tibetan language. Because the gods live in the mountains.

I have always seen myself as an ocean person. I love the rhythm of crashing waves, the smell of salt in the sea air, the white foam breaking into froth around my feet, and tugging me along as it leaves.

And then I went to the Lahaul and Spiti valleys and everything changed inside of me. I became a mountain soul. Those who have been there will understand what I mean.

The Lahaul and Spiti district in India’s northern state of Himachal Pradesh is one of the most beautiful places I have travelled to. Remote and untouched, its offroad route is accessed through neighbouring Kinnaur district if coming in from the Shimla side. When exiting, it continues to Manali to form a loop. Kinnaur and Lahaul are both verdant and green. Sandwiched between them, Spiti, in stark contrast, is a high mountain barren desert perched on the soaring Himalayan range, wild and windswept.

Starting with today, I will be posting a photo diary trilogy of Kinnaur, Spiti, and Lahaul over the coming three weeks. Care to join me and let your soul fall in love with the mountains too?

Note: Lahaul and Spiti used to be two separate districts and were merged into one in 1960. For the purpose of this trilogy, they are treated separately because of their geographic distinctiveness.

The road from Shimla to Kinnaur winds its way past Padam Palace in

Rampur Bushahr. Built in 1919 by His Highness Maharaja Padam Singh Sahib

Bahadur, the 122nd king of the Bushahr dynasty who ruled this part of the world, it is in the Indo-Saracenic style.

Part-hotel [Nau Nabh Heritage Hotel] and part-home, I managed to find the guard and asked him to show me around. Which he kindly did, taking me through ornate living areas punctuated with massive oil paintings of past maharajas and stained-glass windows, wax-polished wooden staircases, and some spooky backhouses. At one time this place must have been filled with familial laughter. Now it lay all silent. Still lovely, but a little lonely.

Land of mountains, bathed with waterfalls. Kinnaur’s countless springs

and rivers are drinkable. You will see many a local having a hearty sip

by their side.

One of Himachal’s most photographed mountain roads. Bucket list. Check.

My first night is at a camp in Rakcham. As soon as the sun set, the

power was turned off. It was also freezing cold. Under such

circumstances, getting up at the crack of dawn for a walk along the

Baspa river, a tributary of the Sutlej river, was a piece of cake. And

so rewarding. Maybe they turned off the electricity on purpose to force

city-dwellers connect with nature. The thought made me chuckle aloud.

Mountains do that to you. It was slowly dawning on me that they made me smile for no reason at all and for every reason as well.

View around my camp in Rakcham.

Isn’t she beautiful. I asked her how old she was. She said she did not

know, but she had been around for a very long time. Natives of Kinnaur,

recognizable by their green caps, are known as Kinners and according to

mythology are half-god half-human. This lady certainly was one.

Chitkul is the farthest one can travel to without a permit in Kinnaur.

From this point on, it is 90 kilometres to the Tibet border; an area

controlled by the Indo-Tibetan Border Police Force. I dropped by to say a

thank you to our soldiers for always, 24/7, taking care of us and

guarding us. Next on my non-existent agenda was a chai in the shadow of my country’s flag by the gurgling ice-blue Baspa river.

Pride of place in Buddhist Chitkul Village belongs to the non-Buddhist

500-year-old Mathi Devi Temple. A prime example of the region’s

syncretic culture. That carving in my hand was part of the goddess’

paraphernalia a local silversmith was lovingly making for the inner

sanctum’s refurbishment.

It gets really cold in Chitkul in the winters. High up in the Himalayas

at 3,450 metres, its approximately 900 villagers move to the lower

slopes when everything starts to freeze—their wooden houses with slate

roofs locked till spring. In the centre of the village is the Kagyupa

temple, a bright red and yellow Buddhist temple.

Lunch at ‘Hindustan ka Aakhri Dhaba’ aka India’s Last Dhaba in Chitkul.

No one, and I mean it no one can make rajma chawal the way the dhabas

[roadside eateries] in Himachal do. They have absolutely aced the art.

Kinnaur’s most popular and lucrative produce: its apples.

They were everywhere during my travels. Hanging from festooned trees in

their millions. Packed in thousands of crates on the curbs. Kinnauri

apples are especially in demand for their long shelf life. Nature’s

candy.

Before the Bushahr royal family [erstwhile rulers of Shimla and Kinnaur

from 1412 to 1948] moved to Padam Palace on the Shimla Hills, they used

to live in this fantastical multi-storeyed stone and wood structure

called Kamru Fort in Sangla. Their home is now a temple dedicated to the

goddess Kamakhya from Assam. Sangla, by the way, means ‘Pass of Light’

in Tibetan language.

On to Kalpa.

‘Suicide Point’ on the left of the above image lies just outside Kalpa.

It is a tourist landmark. Now why would someone want to kill themselves

when surrounded with so much beauty beats me!

From Suicide Point a road with spectacular views leads to Roghi Village,

an authentic Kinnauri village replete with traditional homes and

temples, and a Narayana Temple. The temple is reached by very many steps

going down the hill. Be warned. Getting back to road level is the tough

part.

Travellers describe Kalpa as the crown jewel of Kinnaur. It is not

without a reason. High up at 2,960 metres, the small village is

navigated through steep angular roads leading to the white-washed 11th

Century Hobulangka Gompa. A short walk downhill is the pagoda-styled

Narayan Nagin Temple dedicated to goddess Durga with life-sized wooden

tigers fiercely guarding the entrance from the wings.

Can you see that little needle-shaped rock on one of the summits in the

centre of the above image? That’s Kinner Kailash, a 79-feet-tall Shiva

linga sacred to both Hindus and Buddhists, and the very essence of

Kinnaur. Devotees believe its sighting is auspicious. I guess it abodes

well for my journey ahead.

– – –

Next week, I will be writing about my travels through Spiti. I hope you join me again.

[Note: This blog post is part of a series from my 15-day solo road trip to Kinnaur, Spiti, and Lahaul in Himachal Pradesh. To read more posts on my Himachal Pradesh travels, click here.]

part 2: the spiti trilogy: spiti, the barren side of life and himachal

Buddha statue in Langza Village. Because the gods live in the mountains.

Welcome to part 2 of my photo diary trilogy on Kinnaur, Spiti, and Lahaul.

This week’s post is about Spiti, a cold desert biosphere in the rain shadow area of the Himalayas bordering Tibet. India’s monsoons do not reach here. Even if they do manage to squeeze their way past the soaring peaks, all they are able to muster is a drizzle. The summers are always dry. The winters are covered in thick snow and ice.

None of which is conducive to agriculture except if carried out on the banks of the Spiti river. The land is otherwise brown and barren, its moonscapes strewn with sand and boulders. Nestled in this arid bleakness are countless ancient monasteries, bedecked and bejewelled with Tibetan Tantric Buddhist iconography. These pockets of sanctity serve as places of refuge, giving strength and meaning beyond a difficult life.

Come along with me to Spiti.

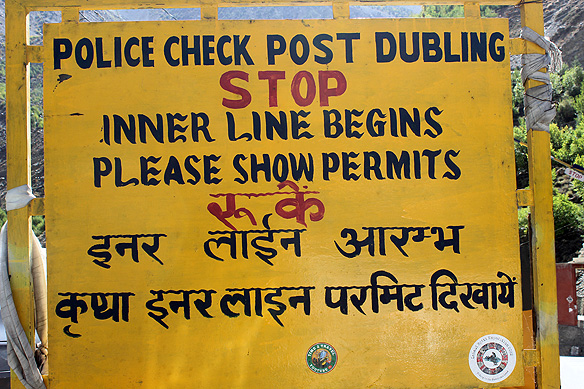

Since Spiti adjoins the country’s border, foreigners need special

permits to enter the valley. Indian citizens, however, only need to show

their identity cards.

What’s a visit to Himachal Pradesh without a bowl of veg maggi from a

street-side stall. This was lunch at the dhaba by the Khab bridge. The

bridge spans the confluence of the Sutlej and Spiti rivers.

Ka-loops’ hairpin bends en-route to Nako.

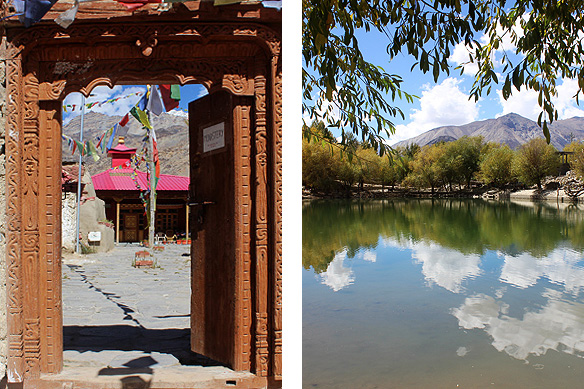

Nako, one of the highest villages in Upper Kinnaur facing Tibet, is

where the Kinnaur valley ends and the Spiti valley begins. With just

some 500 people calling it home, it comprises of a monastery originally

built in 1025 and restored post the 1975 earthquake, and a man-made lake

lined with willow trees and prayer flags. There are no doctors, no

electricity, no internet. Welcome to the high mountains of the

Himalayas.

Picture postcard Spiti.

Tabo is all magic! Pure Tibetan Tantric Buddhism magic. The holiest and

oldest continuously operating monastery in India, it was built in the

year 996 and is often described as the ‘Ajanta of the Himalayas.’

Reason? Inside the nine mud temples is an overload of ancient thangkas,

manuscripts, effigies, and murals. Unfortunately, photography is not

allowed.

There is another feature which sets the monastery apart from others. Instead of being perched high up on a mountain summit, Tabo, designed as a fort, lies on the banks of the Spiti river surrounded by apple orchards planted by the monks.

India’s only ‘mummy’ sits in a small room in Gue Village near Tabo and

the Indo-Tibetan border. Meet Sangha Tenzin, a lama who decided to

preserve his body naturally 500 years ago. He first starved himself,

then ate poisonous nuts, and finally ran lit candles along his skin to

dry it out.

He was forgotten to the world right until 1975. After the earthquake exposed his tomb the Border Police housed him in a small temple where the likes of tourists and pilgrims drop by to say hello.

Part of the Langza-Hikkim-Komic circuit, the highly atmospheric Tangyud

Monastery in Komic is a relatively new structure—1975. The original

edifice used to be in Hikkim, but was destroyed in the Spiti earthquake.

What it lacks in historical significance, the monastery more than makes

up for in location. High up at 4,587 metres, I felt on top of the

world, literally, with 360-degree views for hundreds of miles. What is a

view without a meal, do I hear you say? Next to the monastery is the

world’s highest organic restaurant.

No trip to Spiti is deemed complete without a postcard sent from the

world’s highest built-up post office in Hikkim set up in 1983 by the

local postmaster. Sans any internet or phone connectivity, it is the

only way the village, and those around it, stay connected to the rest of

the world. When winter falls, the post office shuts its services till

next year’s spring.

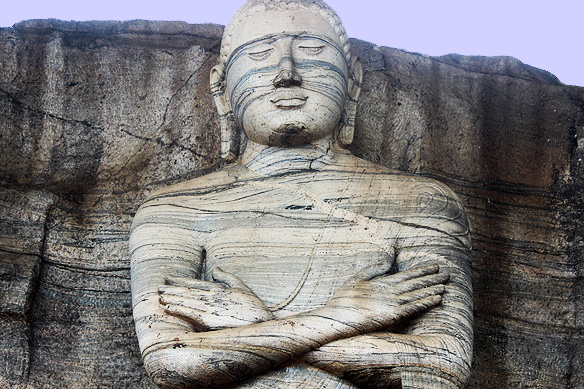

Nearby is the Langza Village with its monumental statue of Buddha. Popularly known as Fossil Village, the whole area once lay under the prehistoric Tethys Ocean. When the tectonic plates collided, these rolling highlands rose up 4,420 metres to become part of the Himalayas, the roof of the world. The earth here is filled with marine fossils. Though often sold, may I request you do not buy or pick up any. Let them stay where they belong so that others can also enjoy their million-year-old stories.

The very symbol of Spiti culture and the valley’s most famous monastery

is also its largest, one of the oldest, and a centre for learning.

Established in the 11th Century by the founder of the Tibetan Gelugpa

sect, the Ki Monastery is where the region’s lamas have historically

been trained. Attacked and rebuilt many times over, it is high up in the

Himalayas at 4,166 metres …

… My eyes were, however, on the peak overlooking the

monastery—Tashigang, covered with a mass of windswept prayer flags—which

a dirt road took me to under a powder-blue sky.

Chicham, Asia’s highest suspension bridge towers over a 100-metre-deep

gorge. Before it was built in 2017, the only way to get to the villages

on the other side was by a pulley and ropeway system. Together with

Spiti’s other roads and bridges, it was built and is maintained by the

Border Roads Organisation, a part of the Indian government’s Ministry of

Defence.

Dhangkar, my destination, literally means Fort on the Cliff. ‘Dhang’ is

Tibetan for cliff, in this case one at a height of 3,894 metres, and

‘Kar’ is fort. Capital of the 17th Century Nono rulers of Spiti, its

main claim to fame today is its crumbling 12th century monastery,

and the ruins of a mud brick fort. At one time the entire town’s

population lived within its fortified walls overlooking the confluence

of the Pin and Spiti rivers, and protected themselves by throwing stones

at invaders.

I met one of the monks inside the old monastery who gave me a cup of seabuckthorn tea and let me poke around the shadowy rooms. He was the second son in his family; his parents had ‘given’ him to the sangha [Buddhist monastic order] when he was a child. It is a practice that still prevails. I asked him if he was happy being a monk. He told me that for the longest time he had envied his elder brother for having a wife and family, a home, a career. He would ask himself why not him. His own whole life had been spent inside the monastery walls. But he was okay with it now. He had made peace with a destiny he had never had a say in, and could never change.

Acceptance. I sipped my tea in the dark windowless chamber lit by yak butter lamps, the word reverberating inside of me.

One of my homestays was in Lalung.

Lalung means God’s Land. I had a pretty room overlooking the mountains

and my host was a lovely lady whose husband cooked delicious meals.

Before tucking in for the night, I decided to take a stroll through the

village until I was chased away by a large black hairy yak returning

home, and a 5-year-old had to chase the yak away for me.

As always, it was subzero at night. The solar lights had died out as well. The following morning, after dousing myself in deo, I apologised to my host for not bathing. She laughed out aloud. “No-one bathes here every day. Once winter falls, the pipes will freeze. If there is water to cook, that is a blessing. By the way, do not forget to visit the monastery. I will tell the lama to meet you there with the key.”

Lalung Monastery is one of those jewelled pockets which Spiti is packed

with and has a fantastical tale of its own to boot. Gilded and painted,

its dark rooms are said to have miraculously cropped up in the 10th

Century, next to a seabuckthorn tree that the village’s spiritual leader

had given to the villagers. The tree still grows in the monastery

complex.

On to Pin valley which was declared a wildlife reserve in 1987. It is

renowned for its snow leopards and Siberian ibex which are best sighted

when the area is blanketed under many feet of snow. On an autumn

morning, this was what it looked like.

Just a slightly rickety handmade suspension bridge across the Pin river that I decided to take a stroll on.

Spiti’s second oldest functioning monastery is in Kungri Village and

dates to 1330. I found myself to be in time for a chanting session

carried out by monks, nuns, and novices—the whole commune—as part of a

religious event’s grand finale. What a performance it turned out to be,

replete with traditional drums and trumpets accompanying sonorous sacred

mantras.

And back again to Kaza.

At 3,800 metres, Kaza, Spiti’s commercial centre and base for exploring the region is higher than even Leh [3,500 metres]. The old town, Kaza Khas, is criss-crossed with narrow crowded lanes, souvenir shops, and quaint cafes serving piping hot thupkas and seabuckthorn tea, with bikers in black leather revving in and out loudly. In Kaza Soma, the new town, is the Eight Stupas and the bright and colourful Tangyud Monastery [2009]; the latter rarely visited by tourists.

– – –

I hope you enjoyed the above virtual tour of Spiti and are tempted to explore it in person, someday soon. Next week I will be writing about Lahaul, the third and final part of the trilogy. Wishing you happy travels. Always.

[Note: This blog post is part of a series from my 15-day solo road trip to Kinnaur, Spiti, and Lahaul in Himachal Pradesh. To read more posts on my Himachal Pradesh travels, click here.]

india travel shot: shimla’s toy train

Imagine—a cross between a train and a car, a rail motor car as it is called, hurtling over towering Roman arched bridges and through tunnels dug deep into dense rocky hills, past pristine forests and verdant valleys. 103 tunnels and 969 bridges to be exact, of which the world’s highest multi-arch gallery bridge is one. Every now and then it stops at quaint railway stations in little villages. Care for a bite?

The fantastical contraption in the image above, straight out of the pages of British Raj in India, is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site ‘Mountain Railways of India’ since 2008. No trip to Shimla could be deemed to be complete without the inclusion of a journey in it in the itinerary. Not 120 years ago. And not now.

Fully-functional to-date, the 2 feet 6 inches narrow-gauge railway, covering a distance of 96.6 kilometres past 18 stops from Shimla to Kalka, was built by Herbert S. Harington between 1898 and 1903. It had a crucial responsibility. To connect Shimla, British Raj’s summer capital in India with the rest of the Indian railway system, ferrying the bureaucracy to and from the town high up in the hills. It was, and still is, an engineering masterpiece!

Be prepared for endless gasps of wonder as the wind tears through your hair over 5 hours and some 900 curves. By the time you disembark, both the legs and head are a bit shaky. And the heart, aah, that’s guaranteed to be very happy. Ask mine.

Share this:

the complete travel guide to the treasures of sri lanka’s cultural triangle

Welcome to my travel guide on Sri Lanka’s Cultural Triangle told a bit differently—through short photo-essay chapters on the country’s ancient and medieval history.

Of the six UNESCO-listed cultural world heritage sites in Sri Lanka, five lie within the Cultural Triangle in the heart of the country. It is a region rooted in 2,500 years of history and heritage, both sacred and secular, from timeless Theravada Buddhist sites to splendid Sinhalese royal capitals. All surrounded in lush tropical jungles.

Before I write any further, I would like to briefly explain two terms used in this guide which are part of the warp and woof of the country. Theravada Buddhism and ‘Sinhalese.’ Theravada Buddhism is the oldest school of Buddhism and a direct offshoot of Buddha’s teachings. There are five countries in the world which have Theravada Buddhism as their official religion, and Sri Lanka is one of them. Sinhalese refers to the Indo-Aryan ethnic race native to Sri Lanka.

Whilst this guide covers the five UNESCO-listed sites, it also

includes some gems scattered in-between. I hope you find it useful and

it helps put the country’s Cultural Triangle as a seamless whole with

all the dots connected.

[Title photo: 18th Century Mural at Lankatilaka Vihara, Kandy.]

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka’s first capital

- Chapter 2: Sigiriya, the 5th Century rock fortress

- Chapter 3: Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka’s second capital

- Chapter 4: Kandy, Sri Lanka’s last royal capital

- Chapter 5: Dambulla, a Kandyan sacred art masterpiece

- Additional Sites

- Mihintale, birthplace of Sri Lankan Buddhism

- Avukana, ancient Sri Lanka’s finest standing statue of Buddha

- Yapahuva, the 13th Century citadel of a lost city

- Ritigala, a 2,300-year-old Buddhist monastery

- Nalanda Gedige, Sri Lanka’s central point

CHAPTER 1: ANURADHAPURA, SRI LANKA’S FIRST CAPITAL

This is where it all started. UNESCO-listed Anuradhapura, wrapped in sacred chants and colossal stupas, has been the island’s spiritual heart from the day Buddhism was introduced to its shores. Here, traditions and rituals play out, unhindered and unadulterated, just as they were conceived 2,300 years ago.

One of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, Anuradhapura was founded 3,000 years ago. For half of this period, from 5th Century BC to 10 Century AD, it served as the capital of Sri Lanka, and from the 3rd Century BC onward its sacred core. Following King Devanampiyatissa’s conversion to Buddhism, Anuradhapura became the site of the country’s first Buddhist temple and bodhi tree [from a sapling of the original in Bodhgaya, India]. After him, powerful rulers continued the tradition of upping the city’s sanctity by sponsoring gigantic stupas and monasteries.

Of these, the most significant are: Thuparamaya stupa [3rd Century BC], the first Buddhist stupa built in Sri Lanka; Isurumuniya Vihara [3rd Century BC] built by King Devanampiyatissa; Ruwanwelisaya stupa [2nd Century BC] containing 1/8th of Buddha’s relics; Ruins of Lovamahapaya or Brazen Palace [2nd Century BC], a 9-storeyed building for congregational use; Abhayagiri Vihara, a prominent monastic centre, and Lankarama stupa [both 1st Century BC] built by King Valagamba; and Jetavanarama stupa [3rd Century AD], the world’s tallest stupa at 122 metres high when built.

A masterpiece from across the millennia: ‘Man and the Horse Head’ carving in Isurumuniya Vihara [3rd Century BC].

Sacred timeless rituals at Ruwanwelisaya stupa, Anuradhapura’s holiest site.

Thuparamaya is Sri Lanka’s first Buddhist stupa.

Left: Keyhole pond in an ancient monastery [2nd Century AD];

Right: Moonstone detail. Considered one of the finest moonstones in the

country, the above, sculpted in the 7th to 8th Centuries AD is in the

Abhayagiri monastic complex and represents the journey through samsara towards enlightenment.

Abhayagiri stupa was once part of the Abhayagiri monastic centre

established in the 1st Century BC. When Buddha’s tooth relic first

arrived in Sri Lanka from Kalinga, India in the 4th Century AD, it was

housed in this monastery.

Anuradhapura travel tips:

- Recommended number of days: Three days, two nights.

- Recommended stay: I stayed at Amsterdam Tourist Rest, Anuradhapura.

CHAPTER 2: SIGIRIYA, THE 5TH CENTURY ROCK FORTRESS

Although Anuradhapura was the political and spiritual capital of the Sinhalese kings since the 5th Century BC, for a brief period a thousand years later, it moved to a place called Sigiriya. Seventy-five kilometres south, the site was marked by a towering 180-meter-high volcanic rock pillar. The ruling monarch had its facade painted with frescoes of 500 beautiful women and its summit topped with a palace. Sounds fantastical. But it is true—along with a story of greed, ambition, and possible redemption that is equally incredible.

It was the year 477 AD. In Anuradhapura, Prince Kassapa I had killed his father and ousted his half-brother, the legal heir, to become the new ruler. But his subjects and the Buddhist sangha did not take too kindly to it. Forced to leave Anuradhapura, Kassapa I set up a new capital city in Sigiriya and decorated the rock fortress with landscaped gardens and ponds using an advanced system of hydraulic engineering, and a sumptuous palace on the summit entered through huge stone lion paws. In 495 AD his ousted brother returned. Kassapa I killed himself in battle when defeat seemed imminent, and the capital was moved back to Anuradhapura.

Today, Sigiriya is a UNESCO World Heritage Site celebrating both an architectural marvel, and the tale of human frailty behind it.

NOTE:

You may also like to read The Sigiriya Frescoes: King Kassapa I and his 500 Damsels

Sigiriya’s rock fortress: King Kassapa I’s haven, home, and place of hiding.

Of the 500 life-sized Sigiriya damsels painted 1,500 years ago,

this, together with another 17 are all that remain on the monolith’s

facade. Who they were and why they were painted are questions whose

answers are still shrouded in mystery.

Stairs going up the 180-metre-high monolith are a 21st Century

addition. When the fortress was originally built, a pulley-lift system

was used to go up and down.

Ruins of King Kassapa I’s 5th Century palace atop the Sigiriya rock fortress.

Sigiriya travel tips:

- Recommended number of days: One full day.

- Recommended stay: I stayed at Ekho Sigiriya.

CHAPTER 3: POLONNARUWA, SRI LANKA’S SECOND CAPITAL

Anuradhapura fell to the Tamil kings Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola I’s expansionist policies in the 10th Century. And with it, the Anuradhapura kingdom also came to an end. Determined to bring ‘Lanka’ back under Sinhalese control, King Vijayabahu I defeated the invading Cholas in 1070 and moved his capital further inwards to Polonnaruwa, in the hope it would be safer.

Over the next two hundred years and under the aegis of two additional rulers, Parakramabahu the Great and Nissanka Malla, Polonnaruwa blossomed. Exquisite temples, grand public buildings, and water reservoirs turned Polonnaruwa into the island’s most lovely city. The fine craftsmanship is still impressive even after 800 years. Of special importance are the Sacred Quadrangle with the Atadage, Hatadage, Vatadage, Satmahal Prasada, Nissankalata Mandapa, and Gal Pota; Gal Vihara with its granite-streaked Buddhas; Alahana Parivena Monastery with Kiri Vihara and Lankatilaka; Parakrama Samudra Lake which made the kingdom self-sufficient; the seven-storeyed Royal Palace and Council Chamber; Jetavanarama Image House; and Potgul Vihara, a Buddhist temple containing ancient Sri Lanka’s largest library.

However, it wasn’t long before other Indian rulers renewed attacks. Sri Lanka’s second capital fell in 1212, this time to the Pandyan kings who razed Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, paving the way for a new Tamil kingdom with its capital in Jaffna. Polonnaruwa was abandoned, and unlike Anuradhapura, also forgotten.

One of the most unusual depictions of Buddha: the cross-armed standing Buddha at Gal Vihara.

Lankatilaka Image House in Alahana Parivena encloses a towering standing Buddha statue inside.

Established by King Parakramabahu the Great [1153 – 1186],

Alahana Parivena is the largest monastery complex in Polonnaruwa. It is

filled with ponds, stupas, monks’ residential cells, and a monastic

hospital.

Nissankalata Mandapa in the Sacred Quadrangle is the handiwork

of King Nissanka Malla [1187 – 1196]. An inscription states he used to

sit here when listening to recitals of the Buddhist scriptures.

Each of Polonnaruwa’s three great kings had a Temple of the

Tooth Relic built in the Sacred Quadrangle. King Vijayabahu I built the

Atadage, King Nissanka Malla built the Hatadage, and King Parakramabahu

the Great built the ethereal Vatadage [above image].

Polonnaruwa travel tips:

- Recommended number of days: One full day.

- Recommended stay: I stayed at Habarana Village by Cinnamon.

CHAPTER 4: KANDY, SRI LANKA’S LAST ROYAL CAPITAL

Spread around a placid lake flanked by the snow-white Sri Dalada Maligawa, Kandy was the last seat of the Sinhalese kings and final home of the tooth relic. From the day of its arrival in the 4th Century AD, it was believed whosoever had possession of the tooth relic also got to rule the country. As kingdoms and their capitals changed, the relic moved as well. First from Anuradhapura to Polonnaruwa, on to India for short periods, but always brought back, and finally to Kandy where it has stayed.

Though the Jaffna kingdom was flourishing in the north after the collapse of Polonnaruwa, the Sinhalese never gave up on self-rule, despite it being a difficult task. Founded in 1469, their Kandyan kingdom faced new ‘invaders’ now—the Portuguese and Dutch—which it somehow manipulated its way through using diplomacy and military tactics. And it did succeed till 1815, but eventually had to succumb to the British. Right up to its independence in 1948, Sri Lanka remained a British colony.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1988, Kandy’s main attraction is undeniably the Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic [Sri Dalada Maligawa] with its elaborate rituals enveloped in incense smoke and beating drums. In addition, there is the colonial-era Royal Botanic Gardens Peradeniya; the three 14th Century Gampola-era Western Temples of Embekka Devalaya, Lankatilaka Vihara, and Gadaladeniya Vihara; and the exquisitely painted Degaldoruwa Cave Temple. Come evening, a cultural show replete with music, dance, and fire-eaters offers a perfect grand finale to one’s stay.

Kandy’s most hallowed site: Sri Dalada Maligawa, better known as Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic; Above: Evening prayer ceremony inside the temple.

Grand finale of the fabulous cultural show at the Kandyan Cultural Centre.

Left: 14th Century Lankatilaka Vihara decorated with 18th Century Kandyan-era murals and sculptures; Right: Degaldoruwa Cave Temple, the ‘Second Dambulla,’ is a treasure trove of Jataka stories in the Kandyan style.

Left: Royal Botanic Gardens Peradeniya [1821] has over 4,000 species of plants across 147 acres; Right: Two Angampora martial art fighters wrestle it out on a 14th Century wood-carving in the Embekka Devalaya dedicated to the Hindu god Kartikeya.

Kandy travel tips:

- Recommended number of days: Two full days.

- Recommended stay: I stayed at Mount Blue Kandy.

CHAPTER 5: DAMBULLA, A KANDYAN SACRED ART MASTERPIECE

When Anuradhapura had taken on its iconic mantle of a Buddhist sacred city in the 3rd Century BC, another Buddhist tradition also mushroomed across the island—that of forest-dwelling monks using natural rock caves for meditation and congregation. One such was the Rangiri Dambulla Cave Complex, Sri Lanka’s largest and best-preserved cave temple.

The complex may well have ended up as just one of the many others dotted across the hills were it not for the generous royal patronage it continuously received. Its first royal contribution came in the 1st Century BC after King Valagamba took refuge in the caves for 15 years when political usurpers seized Anuradhapura. In 1190, King Nissanka Malla of Polonnaruwa gilded the caves and gave the site additional Buddha statues. The patronage reached a high point in the mid-18th Century under the Kandyan kingdom who sponsored intricate murals on Buddha’s life across the walls and ceilings, covering an area of 2,100 square metres.

Together with 157 polychrome effigies of Buddha, Bodhisattvas, and royal sponsors made of stucco, clay or carved out of living rock, the UNESCO-listed five-cave complex is a stunning visual treat. Even with the crowds of tourists. A treat that is magnified even further through offerings by pilgrims at its altars in a ritual that has stayed unchanged for two millennia.

Nirvana Buddha in the Devaraja Lena or Cave of the Divine King [Cave No. 1] is the oldest effigy in the complex.

Row of seated Buddhas and the Altar in the Great New Monastery [Cave No. 3].

18th Century mural of a scene from Buddha’s life on the Cave of the Great Kings’ ceiling [Cave No. 2].

The whitewashed columns and gables in front of the cave entrances were added by the British colonial rulers in 1915.

Dambulla travel tips:

- Recommended number of days: Half a day.

- Recommended stay: I stayed at Habarana Village by Cinnamon.

ADDITIONAL SITES

In addition to the five UNESCO-listed world heritage sites in Sri Lanka’s Cultural Triangle described above, the area also contains a string of lesser-known gems. Rarely visited by tourists, they comprise both royal and holy sites sheathed in lush wilderness and are worth exploring. These are Mihintale, Avukana, Yapahuva, Ritigala, and Nalanda Gedige.

Mihintale, birthplace of Sri Lankan Buddhism

Some 13 kilometres east of Anuradhapura is Mihintale, a 3rd Century BC pilgrimage site associated with the exact moment Buddhism came to Sri Lanka. Emperor Ashoka in India had recently converted to Buddhism. Keen to spread the word of peace, he sent his son Mahinda, a monk, to neighbouring Lanka which was then ruled by his friend King Devanampiyatissa. On a plateau, up above a hill, Mahinda preached the doctrine to the king, and a country’s spiritual fate was sealed. Mihintale literally means ‘the plateau of Mihindu’ [Mahinda in the local Sinhala dialect]. The monk’s relics were later enshrined in Ambasthala Dagoba to mark the spot.

Next to the plateau is Aradhana Gala, a rocky outcrop, where Mahinda is believed to have landed after flying across the skies from India. Apart from these two key sites, Mihintale is scattered with ancient Brahmi inscriptions, ponds guarded with Nagas [snake deities] and lions, hospital ruins, stupas, and a massive statue of Buddha.

[Nearest town: Anuradhapura. It is recommended you use one of the local guides at Mihintale’s entrance for an in-depth exploration of the site.]

Aradhana Gala [rocky outcrop on left] and Ambasthala Dagoba

[stupa on right] in Mihintale are associated with the arrival of

Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

Avukana, ancient Sri Lanka’s finest standing statue of Buddha

Towering above the intrepid traveller in Avukana village is a 14-metre-high standing statue of Buddha. One of the very few to have survived from Sri Lanka’s ancient annals, its hands are raised in a variation of the abhaya mudra protecting those who seek him. Whilst some historians date it to the 5th Century and King Dhatusena, father of King Kassapa I of Sigiriya fortress fame, others believe it was made in the 8th Century. There is also a legend that the statue was the result of a competition held between a stone-sculpting guru called Barana and his pupil. Avukana’s Buddha was the guru’s creation.

Either way, the granite east-facing Buddha in a tight-fitting meticulously-pleated robe is a masterpiece. Designed using a combination of two styles—Gandhara [from Afghanistan] and Amaravati [from South India]—the colossal effigy would have once stood inside an image house of a temple complex.

[Nearest town: Anuradhapura.]

Avukana’s 14-metre-high standing Buddha is believed to have been

carved out of living rock on King Dhatusena’s orders 1,500 years ago.

Yapahuva, the 13th Century citadel of a lost city

Halfway up a 90-metre-high rock boulder in Yapahuva is a royal complex reached by steep ornamental stone steps snaking their way to it. For 12 years the magnificent citadel, one of Sri Lanka’s most evocative ruins, served as the capital of a 13th Century Sinhalese king called Bhuvanekabahu I. When the Pandyan rulers of South India attacked Polonnaruwa in 1272, Bhuvanekabahu I fled to Yapahuva bringing with him Sri Lanka’s most prized possession: Buddha’s tooth relic [now housed in Kandy].

Here, deep in the jungle, his predecessors had already built a fortress for defensive purposes. Bhuvanekabahu I fortified it even further, and built a temple for the relic in the royal residence. But both his rule and resplendent city were short-lived. In 1284, the Pandyans succeeded in defeating him, as well as taking the relic away. And Yapahuva got entangled in the surrounding forest and was blotted out, except by the monks who came here to meditate.

[Nearest town: Anuradhapura.]

13th Century citadel of Yapahuva with the lion sculpture which used to appear on the country’s former 10 Rupee note.

Ritigala, a 2,300-year-old Buddhist monastery

Wrapped around Ritigala, the highest mountain in northern Sri Lanka, is a Buddhist monastery that goes back to the 3rd Century BC. Legends abound here, from those of royals who took up an ascetic life to Hanuman, the monkey-god in the Hindu epic Ramayana dropping a portion of the herb-rich chunk of the Himalayas on its summit by mistake.

The current version of the hermitage dates to the late-Anuradhapura period [7th – 11th Century] and comprises of a pilgrim route starting at a 2,500-year-old enormous water tank, up stone steps to platforms for meditation and congregation, bridges, resting areas and an Ayurvedic hospital. Bereft of stupas, bodhi trees, effigies or iconography, its monks were famed for practicing severe asceticism—they wore strips of old cloth and peed on embellished urinals. The latter, it is said, served as an expression of disdain for the material world!

[Nearest town: Sigiriya.]

Ancient resting area for monks inside Ritigala monastery.

Nalanda Gedige, Sri Lanka’s central point

Nalanda Gedige is believed to be located at the geographical centre of Sri Lanka. Somewhere between the 8th and 10th Centuries, this momentous location was celebrated with the construction of a stupa, Buddhist image house [in the South Indian Pallava architectural style], and bodhi tree. Many claim to experience a heightened magnetic pull in the quadrangle. Others, an acute sense of serenity.

Usually deserted except for a few local pilgrims, the temple contains some fascinating detailing. These include carvings of gajalakshmi [goddess Lakshmi flanked with two elephants] on the front portal, and a human trio indulging in erotic sex and ganas [dwarfs] on the plinth. In keeping with Sri Lanka Post’s mandate of putting up a letterbox in the island’s cardinal points, a bright red letterbox greets visitors at the site entrance.

[Nearest town: Sigiriya.]

A Hindu temple-styled image house and Buddhist stupa make the

thousand-year-old Nalanda Gedige a unique architectural amalgamation.

– – –

With this, I come to the end of the post and the end of my Sri Lanka series. Wishing you happy travels, always.

Note: I used Visit in Lanka for my transport arrangements.

[This blog post is part of a series from my solo independent travels to Sri Lanka. To read more posts in my Sri Lanka series, click here.]

exploring sri lanka’s coastal towns: from galle to trincomalee

Indian Ocean from the Galle Fort ramparts just after sunset.

For a country whose length and width are merely 435 kilometres and 240 kilometres respectively, Sri Lanka, the tear-drop-shaped Buddhist island in the Indian Ocean has a remarkable variety of coastal towns.

Starting at windswept Galle with its Dutch colonial vibes in the south-west, next in line is the cosmopolitan financial capital Colombo. Then on to Negombo, the sunny Catholic fishing town in the west, to Jaffna in the north which till recently was completely out of bounds to all and sundry. And finally, Trincomalee in the north-east steeped in ancient Tamil culture against the backdrop of surf-worthy waves.

Come along and explore with me Sri Lanka’s five coastal gems, their unique heritages, and what not to miss.

Table of Contents:

- UNESCO-listed Galle: Asia’s largest surviving colonial-era fort

- Cosmopolitan Colombo: Sri Lanka’s financial capital

- Negombo: Catholic churches and a centuries-old fishing industry

- Off-the-radar Jaffna in Sri Lanka’s north

- Trincomalee: Where ancient Tamil culture and colonial rule meet

UNESCO-LISTED GALLE: ASIA’S LARGEST SURVIVING COLONIAL-ERA FORT

Sri Lanka’s most popular coastal town, Galle [pronounced Gaalla] is a romantic windswept UNESCO-listed World Heritage Site on the south-west coast of the country. Considered to be the finest example of a surviving colonial fortified city built in Asia, the 17th Century structure is an impressive amalgamation of Dutch architecture and local traditions. But Galle has been around for much longer. Before the Dutch, the Portuguese had laid an earthen fort here in 1588. And 1,400 years ago, before them, in the 2nd Century AD, Galle was a thriving port trading with Greece, Arabia and China, according to Ptolemy’s world map.

Car-free, the Old Town is lined with columned Dutch buildings replete with gables and verandas, multiple bastions, historic churches, mosques, and a picturesque British-era lighthouse. Come evening, as the sun sets, both locals and tourists alike set out on walks along the ramparts in the company of crashing waves and painted skies.

What not to miss:

Beautifully restored, Galle’s Dutch Reformed Church or Groote Kerk dates to 1755 and is still in use today.

All Saints’ Church was built in 1871 to cater to the Anglican

community. Prior to its building, Anglican services were held at the

nearby Groote Kerk.

Left: Old Gate’s granite plaque is engraved with the Dutch East

India Company emblem and the year 1669 [when the entrance was built];

Right: Lunch at the nearby ‘A Minute By Tuk Tuk,’ an institution of

sorts.

Dutch-era cannon guarding Galle Fort’s fortifications.

Originally a Portuguese earthen structure, the fort was fortified in

1663 by the Dutch who added 13 bastions made of coral and granite.

The Dutch sea-wall [1729] together with Sri Lanka’s oldest

lighthouse [1848] and Meeran Jumma Masjidh [1907] make for a splendid

view.

Just outside UNESCO-listed Galle Fort are two attractions well worth a visit: Kosgoda Sea Turtle Conservation Project and the Nichiren Buddhist Japanese Peace Pagoda.

Where to stay:

I stayed at Arches Fort inside Galle Fort, an 18th Century Dutch home turned into a hotel.

COSMOPOLITAN COLOMBO: SRI LANKA’S FINANCIAL CAPITAL

No other city gives one a better opportunity to understand Sri Lanka from a 21st Century Sri Lankan lens than Colombo. Often underrated and sidelined by travellers, Sri Lanka’s financial capital is a microcosm of the country. The difference being its rich heritage has not morphed into purely tourist attractions. They are still a part of indigenous life.

Take for instance Kelaniya Raja Maha Viharaya, the 2,600-year-old temple which Buddha himself is believed to have visited and gifted a gem-encrusted throne to be embedded inside a magnificent snow-white stupa. Or the Gangaramaya Temple funded by citizens across faiths and used as a meditation hub. Then there are ancient Tamil Hindu temples, and colonial churches from Dutch and British eras that are in use to date, with Galle Face Green, the city’s social meeting place laid out in 1859. For the perfect wrap, take a heritage walk in the historical Fort and Pettah districts for loads of quirky stories and unexpected minutiae!

What not to miss:

Reclining Buddha in the Kelaniya Raja Maha Viharaya. The temple

site was consecrated in 580 BC and is associated with Buddha’s third and

final visit to Sri Lanka.

Seema Malaka, part of the 19th Century Gangaramaya Temple, was designed by Geoffrey Bawa and funded by a Muslim couple in memory of their son.

Colombo’s Fort and Pettah [Old Town] were first developed by the

Dutch and, thereafter, by the British. Left: Jami Ul-Alfar Mosque in

Pettah [1909]; Right: Cargills Department Store [1906] entrance in Fort.

A pair of 9th Century bronze sandals, for a [now missing] 3-metre-high Bodhisattva, Colombo National Museum. The museum was established in 1877 and is the largest in the country.

I was here: At the Wolvendaal Church [1757]. Graves of 18th Century Dutch men and women cover the church floor.

Sri Lanka’s emblem at Galle Face Green, a strip of manicured lawns facing the Indian Ocean.

Where to stay and how to explore:

I stayed at the Cinnamon Red [it has awesome views] and explored Fort and Pettah with Colombo Walks.

NEGOMBO: CATHOLIC CHURCHES AND A CENTURIES-OLD FISHING INDUSTRY

Forty kilometres north of Colombo is a sunny sleepy Catholic fishing town called Negombo. The proverbial seaside escape, it is built around a centuries-old fishing industry, which still serves as its lifeline, and a fishing community which converted to Catholicism under Portuguese evangelism in the 16th Century. But it is not its beaches which are its draw-card. Rather, it is the Muthurajawela Wetlands bordering the coast, filled with a prolific birdlife and cheeky Toque Macaques [Old World Monkeys], to which travellers throng to.

Predominantly Sinhalese, Negombo also served as a port of call for Arab vessels from the 9th Century onward leading to the introduction of Sri Lankan Moors into the country’s populace. Tourist itineraries reflect Negombo’s secularism with stops at places of worship across different faiths including the atmospheric Angurukaramulla Buddhist Temple and neoclassic St. Mary’s Church, the vibrant harbour and fish market, followed with a gentle cruise down the Negombo Lagoon.

What not to miss:

One of Negombo’s loveliest churches, the neoclassic St. Mary’s

Church was completed in 1922. If you are lucky, you just may get to

witness a Sri Lankan catholic wedding in full ceremony.

All that remains of the 17th Century Portuguese-initiated

Negombo Fort is a small part of the rampart and a recessed gateway. In

the late-19th Century the British demolished the fort to build a prison.

Close to the fort and at the mouth of the Negombo Lagoon is the

town’s lifeline: Its fishing harbour and fish market. An industry that

has survived centuries.

No trip to Negombo is complete without a boat safari in the

Muthurajawela Wetlands, complemented with a fruit spread and Toque

Macaques [Old World Monkeys] for company.

Angurukaramulla Buddhist Temple is a riot of vibrant murals and

effigies recounting Jataka stories and scenes from Buddha’s life.

Snack stall at Negombo Beach – the local way.

Where to stay and how to explore:

I stayed at the Terrace Green Hotel & Spa and explored Negombo with Capital Tuk-Tuk Tours.

OFF-THE-RADAR JAFFNA IN SRI LANKA’S NORTH

One of Sri Lanka’s best kept secrets is Jaffna, a medieval Tamil city perched on the northern-most tip of the island, defiantly rising above gunned-down homes and buildings. Inaccessible for 26 years to both locals and foreigners, the city was the epicentre of the LTTE-Sinhalese civil war which lasted from 23 July, 1983 to 19 May, 2009. It is only in the last 15 years that normalcy has returned to it, revealing sights from its role as the capital of the once invincible Jaffna Kingdom [13th to 17th Century] and subsequent four hundred years of colonial rule, punctuated with a smattering of odes to its hero-king Cankili II.

Jaffna’s highlights include the famed Nallur Kandaswamy Temple and Manthirimanai, the ‘Abode of the Minister,’ along with the majestic pentagon-shaped Jaffna Fort. What adds to Jaffna’s charms is that its rich Tamil heritage set against a stark coastline extends beyond the city, into Jaffna peninsula and a string of isles on the Palk Strait.

What not to miss:

Nallur Kandaswamy Temple, Jaffna’s cultural and spiritual hub,

dedicated to the Hindu god Murugan [Shiva and Parvati’s elder son].

In memory of Jaffna’s hero: Jaffna Kingdom’s last king, Cankili

II, who valiantly fought against the Portuguese in 1619, but lost.

A blend of European and Dravidian architectural styles,

Manthirimanai, the ‘Abode of the Minister,’ is part of Jaffna Kingdom’s

ruins.

The 400-year-old pentagon-shaped Jaffna Fort is inexorably tied

to the city’s colonial and modern history: From the arrival of the

Portuguese, Sri Lanka’s first colonial rulers in 1619, to the civil war

which ended in 2009.

Many of Jaffna’s fisherfolk are Catholic because of the

large-scale conversions carried out by the Portuguese in the 17th

Century.

Established in 1933, Jaffna’s Public Library was once one of

Asia’s largest libraries with an extensive collection of ancient texts.

Though most of these were burnt during the civil war, the library is

slowly finding its mojo back.

Where to stay and how to explore:

I stayed at Jaffna Heritage Hotel and explored Jaffna with Dilushan of Elite Travels.

NOTE:

You may also like to read Jaffna: The Unexplored North of Sri Lanka [detailed post]

TRINCOMALEE: WHERE ANCIENT TAMIL CULTURE AND COLONIAL RULE MEET

Trincomalee, the English corruption of ‘Thiru-kona-malai’ meaning ‘Lord of the Sacred Hill,’ refers to the Hindu Shiva temple which stood in the city since the 6th Century. Known as the Koneswaram Temple Complex, ancient texts described it as a “Dravidian-styled temple with a thousand pillars” and “Mount Kailash of the South.” Its edifices were destroyed and used as building blocks by the invading Portuguese in 1622 for their fort, which the Dutch later expanded. Apart from Koneswaram, Trincomalee houses two other sacred temples: the 11th Century Pathirakali Amman Temple decorated with multi-coloured effigies on its columns and ceiling, and the Salli Muthumariamman Kovil on Uppuveli Beach.

Whilst ancient Tamil culture has always been an integral part of Trincomalee’s heritage, its four-hundred-year-old colonial history is just as much a part of it, even if it was at the expense of the former. The two mismatched warring elements today sit side-by-side against some of Sri Lanka’s best surfing beaches.

What not to miss:

Salli Muthumariamman Kovil facing the famed Uppuveli Beach is dedicated to Amman, the Hindu goddess of rain.

Filled with amazing colourful effigies from Hindu mythology,

Pathirakali Amman Temple or the Kali Kovil was enlarged by King Rajendra

Chola I of Madurai in the 11th Century. Don’t forget to look up!

Trincomalee’s oldest temple, the 6th Century BC Koneswaram

Temple, was attacked and destroyed by the Portuguese in 1622. With its

debris, the colonial rulers built Fort of Triquillimale [later renamed

Fort Fredrick by the Dutch].

Left: Dutch-era gateway inside Fort Fredrick [1675]; Right:

Statue of Shiva at the entrance of the restored 1952 Koneswaram Temple

inside Fort Fredrick.

Trincomalee War Cemetery with graves of the British soldiers and their allies who died during World War II.

Velgam Vehera aka Natanar Kovil, a 4th Century BC Buddhist

temple on the outskirts of Trincomalee. The temple has historically been

worshiped by both Buddhists and Hindus alike.

Where to stay:

I stayed at the Trinco Blu by Cinnamon. Its chalets are right on the beach, and the breakfast spread is fab.

– – –

Tempted to now travel to Sri Lanka’s coastal towns? Wishing you happy travels, always.

Note: I used Visit in Lanka for my transport arrangements.

[This blog post is part of a series from my solo independent travels to Sri Lanka. To read more posts in my Sri Lanka series, click here.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.