Rani ki Vav

Rani ki vav, arguably the world's most impressive stepwell.

Simply put, Rani ki vav, or "The Queen's Stepwell," in the little

northern Gujarati town of Patan, is one of the foremost man made wonders

of India. The stepwell is generally thought to have been built by Queen

Udayamati of the Solanki dynasty as a memorial for her deceased

husband, Bhimadeva I, in the late 11th century. At the time, the

Solankis ruled over much of what we now refer to as the state of

Gujarat, and their reign is often viewed as a golden age in the history

of the region.

While the physical remains from the period are not great in number, the

few Solanki buildings which still exist are truly exceptional. Patan,

once known as Anhilwara, Anahillapura, Anahillavada, or any one of

several other names, was the capital of the Solanki kingdom, though the

vast majority of the traces of Solanki rule have long since been swept

away, starting in the 13th century when the city was sacked first by

Qutbuddin Aibak of the Delhi Sultanate, and then, later in the same

century, by his successor on the throne of Delhi, Allauddin Khilji. In

the 21st century, there is little in the dusty, unassuming little city,

other than the step-well of course, to remind one that Patan was once

the center of an empire.

That makes a visit to Rani ki vav all the more startling: In the middle

of nowhere, in a city which, though certainly not unfriendly or

particularly backwards nonetheless does not feel like it should have

ever been at the center of anything, one suddenly comes across one of

the most awe-inspiring man made sights in the country. This is in part

because the well was far more than a merely functional building. In

northwest India, where rainfall is scanty and water tables are deep on

account of the regions sandy soil, the building of a step well was

viewed as a meritorious act, and the wells themselves as places of

worship. It can also be said that the well, like all monuments, was a

means by which the Solankis could physically demonstrate their immense

wealth and power, something which it certainly does: Even when there are

so few remaining physical reminders of the Solankis existence, Rani ki

vav all by itself indicates that theirs was an age of incredible

artistic prowess.

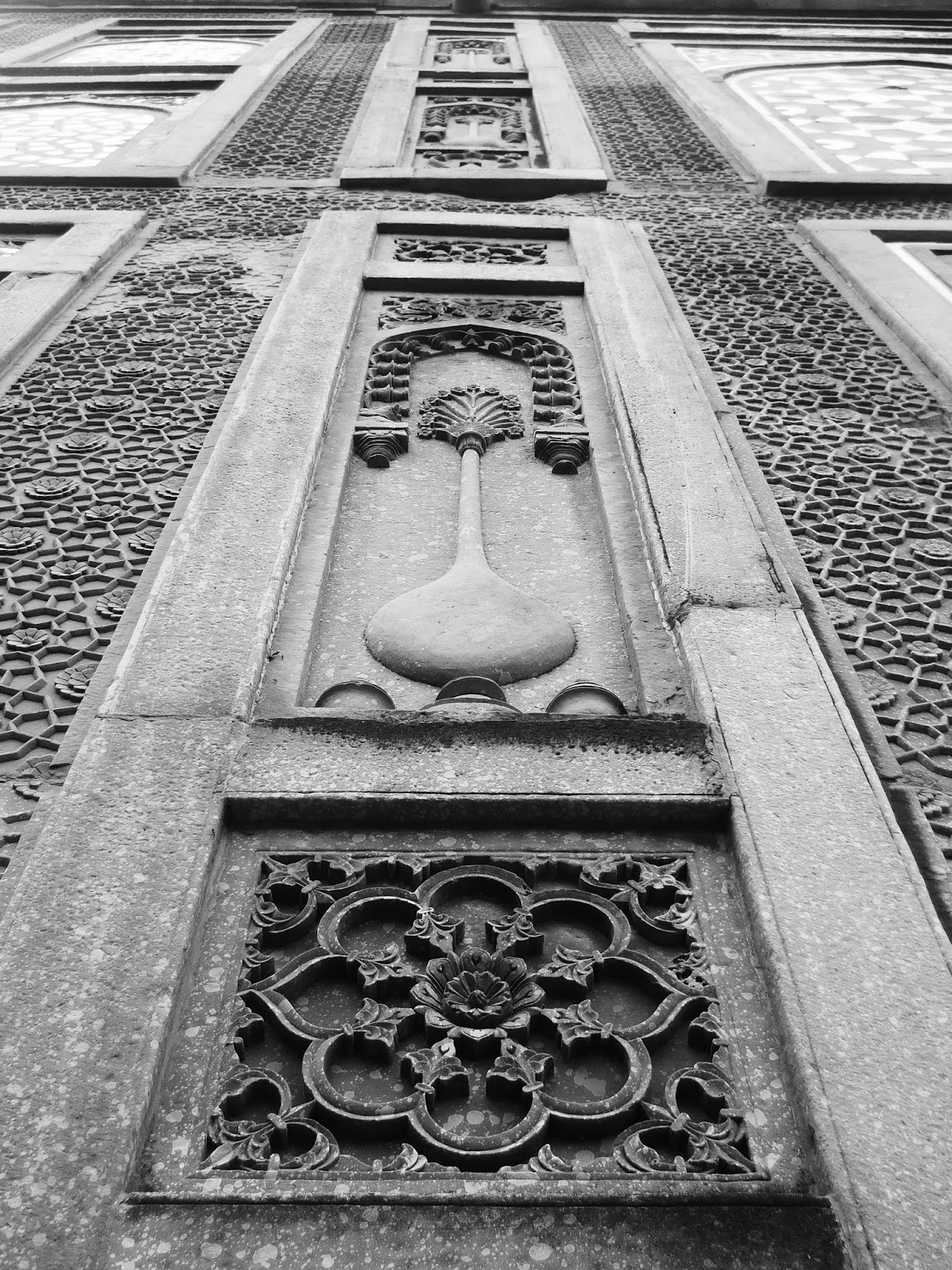

Rani ki vav is to step wells what the Taj Mahal is to tombs and what

Mehrangarh Fort is to fortresses. While there may be larger step wells

in India, there aren't many, and those that are don't boast anything

approaching the almost hallucinogenic profuseness and technical skill of

Rani ki vav's incredible carvings. Yet, it seems that because

stepwells are a relatively obscure form of architecture, Rani ki vav

will remain relatively little known well into the foreseeable future

(despite the having having been made into a UNESCO world heritage site

just earlier this year.)

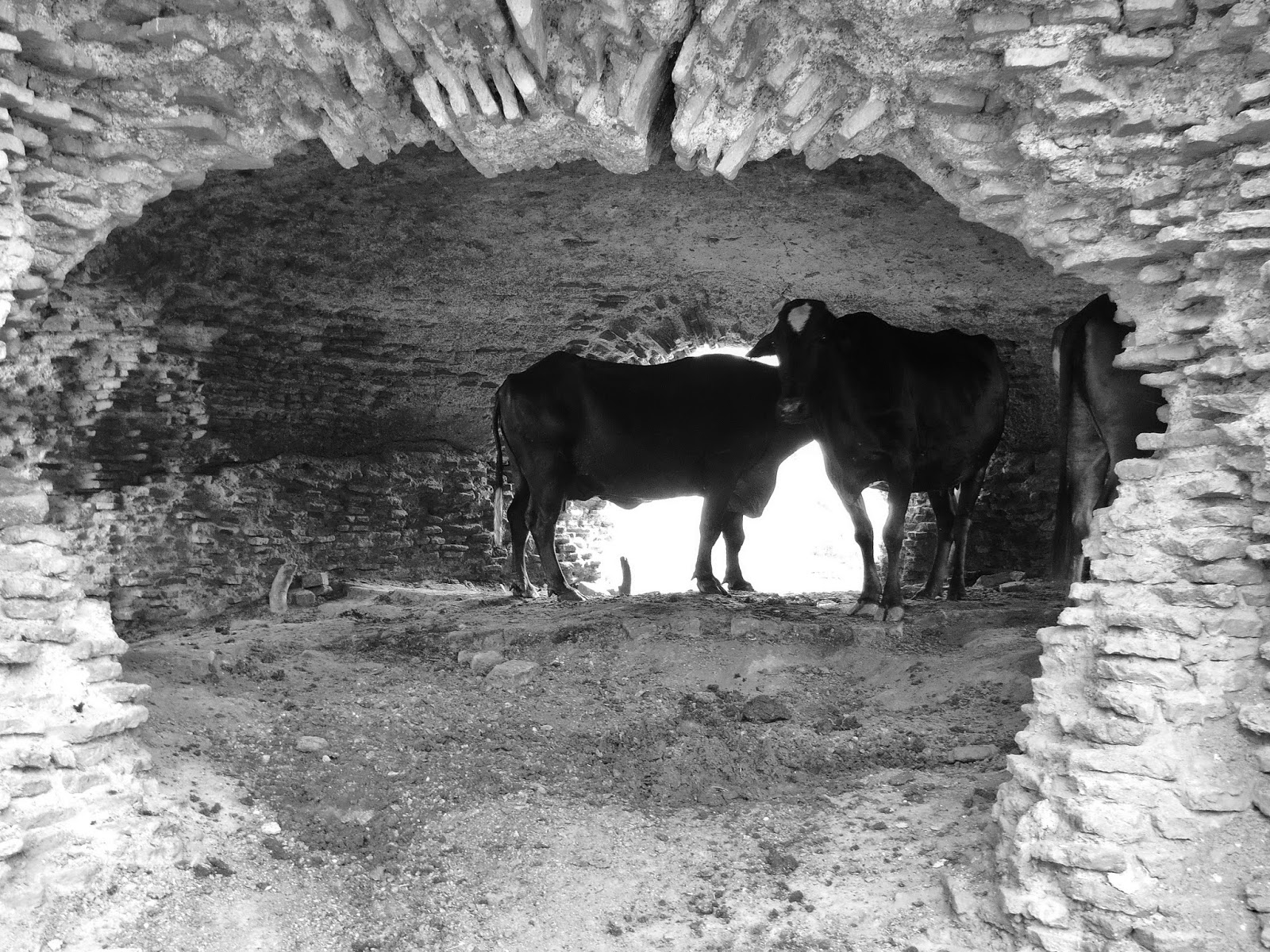

For centuries, the well was abandoned, during which time it filled

almost entirely with silt. Much of what remained above ground by the

19th century was carted off and used as building materials for other

constructions. It wasn't until 1986 that the A.S.I. began the process of

excavating and conserving the monument. Given how little care the

stepwell has received since the 13th century, it's a wonder that there's

anything left at all. Yet, even in its ruinous condition, Rani ki vav

projects an incredible opulence, and nearly a thousand years ago, when

the building had yet to face the ravages of time and Muslim invaders, it

must have been among the very grandest sights in India.

Looking into the step well. In its original form, the well would have

had seven terraces, each on a separate level, along with a large torana,

or ceremonial gateway, and so would have looked very different from

what you see here. There would have been considerably more shade inside,

and the lowest levels would receive very little direct sunlight except

in the middle of the day. Over time the torana has disappeared,

and the uppermost terrace has been stripped away, leaving only remnants

of the lower six. While even after a millennium of neglect the sheer

quantity of sculpture within the step well is an amazing thing to see,

when it was built Rani ki vav apparently contained close to twice as

many statues. At the back, or western, edge of the construction is the

primary well shaft, the deepest part of Rani ki vav, which is now

annoyingly off limits to the public. This was dug deep enough to allow

access to the water table of the Saraswati River, which even as late as

the 1980s still replenished the well, though the shaft has since gone

dry. In front of the well shaft is a rectangular reservoir. A long

flight of steps, with seven separate landings for each terrace, leads up

from the reservoir, while two small secondary staircases (both, again,

out of bounds) lead down from just in front of the well shaft. When the

stepwell was still filled in with silt, the only thing in the picture

above that remained unburied was the topmost few meters of the well

shaft. Until the 1980s virtually all of the statues and columns pictured

here were underground, encased in silt.

As a tourist site Rani ki vav leaves much to be desired. Visiting the

step well is frustrating, as no matter where you're going in Gujarat,

getting to Patan requires quite a long detour, and once you get there,

you find that much of the actual structure is blocked off and, even

worse, impossible even to see. One can go some of the way down into it,

but an awkwardly placed railing not only prevents you from going

further, but also stops you from getting a view of the most impressive

parts of the step-well (a problem which could be easily fixed if the

A.S.I. would simply move the railing forward a few feet.) Both the main

reservoir and the well shaft, the two deepest and therefore most

impressive parts of the building, are off limits. My experience of

visiting was made more annoying by a security guard who insisted on

being an impromptu and largely ignorant ("This vav is 5000 years old")

guide in order to try and get rupees out of me...The really was no

getting away from him either, given it was just him and me down in the

pit at 11 A.M...no other tourists were willing to brave the heat...

Still, these things shouldn't discourage one from visiting the stepwell.

What one can see is still incredible, and even in its ruinous state and

with the flaws in its presentation by the A.S.I, Rani ki vav is still

in my estimation one of the very most spectacular archaeological sites

in all of India.

This is an eastward facing view from the top of the well shaft, which

gives a good impression of just how much of the structure is missing.

Profusely carved columns and niches inside Rani ki vav, looking straight

towards the back of the well shaft. The statue in the middle is Vishnu

reclining on the serpent Shesha, while the niche to the right depicts

Ganesh and his consort, and that to the left shows Vishnu and Lakshmi

seated on Vishnu's mount Garuda.

Looking directly down into the well shaft. It really is a shame that one

is not allowed down there, especially since the shaft is the most

intact part of the whole stepwell.

The incredible walls of the stepwell. The lower down one goes, the more

of the statuary remains. However, apparently in some of the niches on

the upper levels, the statues were never installed, implying that the

stepwell was never entirely finished.

More incredible statuary. This view would not have been possible before

the stepwell fell into ruin: What we would be seeing here would be the

bottom of one of the terraces.

Closer on assorted statues.

A view through a stone corridor toward one of the reclining Vishnus at

the back of the well shaft. Vishnu is the primary deity of the of the

stepwell, and a large proportion of the sculptures are depictions of one

of his many forms.

Presumably a depiction of one of the many Gauris, who are different

forms of Parvati, Shiva's consort. Another common motif in the stepwell,

Gauris were worshiped as the center of their own, woman-centric cult.

After sculptures of Vishnu, carvings of Gauris and other forms of

Shiva's consort are the most numerous inside the stepwell.

A somewhat worn statue of a four armed Hanuman about to strike a blow.

Varaha, Vishnu's bore headed incarnation, striking a heroic pose. Note

the goddess on his elbow caressing his snout. The scene being depicted

here is Varaha lifting the Earth Goddess up from the depths of the

ocean.

Durga slays the bore demon, her lion attacking from the side.

A Camphor spirit, as represented by a bathing maiden. Camphor is what

was traditionally burnt in Hindu religious ceremonies. Note the bird to

the left apparently drinking the droplets of water falling from the

maiden's hair.

A naked serpent woman, along with three owls above, and a peacock behind

her legs. The depiction of snake spirits inside the stepwell is

fitting, as snakes are regarded as primarily being water dwellers in

Hindu mythology.

If you ever happen to find yourself in Patan, I would advise that you

try and get to Rani ki vav early in the day. I took the pictures above

at about 11 A.M...which, besides being tremendously hot, was also not

the best time as far as lighting was concerned. In some of the other

more intact stepwells in Gujarat the sun only reaches the lowermost

levels at midday, hence the best light is between 10 A.M. and 12 P.M. I

had thought the same would hold true at Rani ki vav, but it proved not

to be the case, mostly because so much of the original structure no

longer exists, allowing the sun in even into the deepest levels during

most of the day.

Much of my information above comes from the handy Archeological Survey

of India publication on Rani ki Vav by Kirit Mankodi. They sell it for

rs. 30 at the ticket booking window, and it really is worth it.

For more on Solanki architecture, go to: http://evenfewergoats.blogspot.com/2014/09/modhera.html

Kaziranga

The star attraction at Kaziranaga National Park: The Indian one horned

rhino. The park is said to contain about two thirds of the world's

population of the rare beast, so many that it's virtually impossible to

visit Kaziranga and not see dozens of them

One of the very first places I ever went to in India, all the way back

in January 2009, was Kaziranga National Park. By now, as part of

University of Delaware study abroad groups, while leading my own trips,

or while travelling with members of my family, I've visited the park

somewhere in the vicinity of six times. That may sound like overkill,

but, believe me, it's not. I've found that my enthusiasm for the place

has only grown over time.

The reason for this is simple: No one safari in Kaziranga is like

another. Even if you've visited over and over, there is always the

chance of seeing some animal that you've never seen before. And, failing

that, as a repeat visitor you might encounter an animal that you've

seen countless times behaving in some new way that you've never before

observed. By this stage, with six visits to the park I've probably seen

half of the world's population of one horned rhinos (maybe that's an

exaggeration...though 10-20% is not), but, until my most recent visit I

had never had one start to charge my jeep and get warned off by an armed

guard brandishing his Lee-Enfield.

In January, I visited the park with my mom, and, for the first time in

years, took a whole new crop of photos. Bear in mind that all of these

were taken over the course of a single day, illustrating the incredible

density of spectacular animals within the park.

Ghost elephants in the mist. Starting out on a 5 a.m. elephant safari. My mom and I first thought that because of the misty morning we weren't going to be able to see anything. But in the end it turned out that there were so many animals around that not being able to see more than ten feet in front of your face was not that much of an impediment to wildlife viewing

Ghost elephant

Our elephant and mahout

Later the same day, my mom and I took a jeep safari to the Eastern Range

of the park. While the elephant safaris are in some ways more memorable

as experiences, one does tend to see much more on the jeep safaris. We

had a naturalist and birding enthusiast friend of mine, Bitupan Kolong,

riding with us, and he was able to both point out and name plenty of

animals along the way that my mom and I would surely have missed.

Stork billed kingfisher, just outside the park. To someone who really

knows what they're looking for (which is not me) the avian fauna of the

park, especially in winter when migratory birds from all over Asia stop

here, is just as noteworthy as the large mammals.

Some variety of eagle

A classic Kaziranga view: A heard of wild elephants

More wild elephants, with a huge water buffalo in the background just for good measure

Mallards....almost exactly like the ones we have back in my home state of Delaware

The Grey Heron in the back there isn't the star of this shot. The

relatively mundane seeming Bar-headed geese in the foreground just

happen to be some of the world's toughest birds. Migrating to India over

the Himalayas, their journey over the loftiest mountain range on Earth

takes them higher in altitude than any other bird. Scientific studies

have shown them to be able to fly to at least 21,000 feet, while

travelling to and from their nests on the Tibetan Plateau

Wild Jungle fowl, ancestor of the chicken

We got an incredible view of this rhino with an egret on its back...

...especially when it decided it didn't like the look of us and started

to charge. Our armed escort earned his pay on that safari.

Wild elephant

Cormorant

A male elephant with huge tusks, along with a rhino

One of the unexpected highlights of the jeep safari: A romp of otters

(yes, you call a group of otters a romp). They were pretty far away, so

it wasn't possible to get that great a photo, but still, this was

something I had never seen before

Wild water buffalo. Another one of the unsung success stories of

Kaziranga, the park contains something like 60% of the world's wild

water buffalo

So, just to sum this post up: Come to Kaziranga.

Special thanks. From left to right: Our armed guard, the driver, my mom, and Bitupan

The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 4: Living Root Ladders and other uses for living root architecture

Heavy metal living root ladder near the mid-sized Khasi village of Pongtung

First off, for more information on living root architecture, go to The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 1: Bridges of the Umngot River Basin for living root bridges in the Jaintia Hills, The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 2: Bridges near Pynursla for information on the area with the highest concentration of living root architecture, and The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 3: Bridges of the 12 villages for some of the most remote known living root bridges.

This, the final post in my four part series on unknown or obscure living

root architecture, will deal with structures made from living roots

that are not bridges, along with failed or destroyed living root

bridges.

While the living root bridges are by far the most famous variety of

living root architecture in southern Meghalaya, similar techniques have

been used to create a surprising number of other functional structures.

Broadly speaking, these include living root ladders, platforms, and

retaining structures, along with hybrid constructions that are several

of these things at once.

Perhaps the least photogenic, though nonetheless extremely ingenious,

use for the living roots of Banyan trees is in the construction of

retaining structures. While walking on horizontal paths in the Khasi

Hills, which usually hug the sides of steep inclines, one often notices

that there will be Banyan trees directly next to the trails with roots

that seem to be almost holding the slopes up. That is indeed what is

happening, and, as I found out earlier this year, the trees have been

deliberately planted to perform this function. The roots of the tree are

being used to stabilize the slope, rockfalls and landslides being a

major problem in the hill country of Meghalaya. It's well known that

having lots of trees on a hill side can make it more stable due to the

gripping power of tree roots. Banyan trees, given their exceptionally

numerous roots which have evolved specifically to adhere to rocks and

steep inclines, are uniquely suited to this task.

While these structures (which may even stretch the definition of

architecture a tad) are less visually appealing and not as likely to

draw huge crowds of visitors as other forms of living root architecture,

they nonetheless continue to have great practical value. Particularly

at a time when the slopes of the Khasi and Jaintia Hills are under

increased pressure due to unsound farming techniques, the use of Banyan

tree roots as retaining walls could be potentially lifesaving. Projects

for stabilizing hill slopes through the use of conventional retaining

walls is not something that the people of remote Khasi villages would be

likely to be able to complete, as to do so effectively would require

large amounts of construction equipment, not to mention government

funds, which would probably entail outside construction crews. Using

Banyan trees much more extensively than they have been used already

would be both free (saplings would simply have to be transplanted) and,

in the long term, more effective. The roots used in the retaining

structures would only grow stronger and more numerous. The slopes would

get more stable over time.

However, it took me until about two thirds of the way through my long

hike in the Khasi Hills to even notice what these structures were.

Unlike other forms of living root architecture, they don't tend to stand

out very much, and don't look like much more than a tangle of roots in a

photograph. Still, when I return next year, I do intend to map as many

of them as I can.

Another .as yet very rarely visited, form of living root architecture

are living root platforms. I've only personally encountered two of

these, though I know of the existence of a third. They seem to be used

for observation, though more examples would need to be found to say

anything definite. For me, an interesting question is whether or not

platforms have been grown high up in trees (presumably for hunting).

This certainly would be possible, and might mean that I have walked

underneath numerous examples of these structures without noticing.

Finally, there are living root ladders. The use for these is pretty

obvious: When a trail needs to be built over terrain that is too steep

for stairs, the roots of Banyan trees are used to create a vertical

pathway. Confusingly, Khasi languages do not draw a distinction between

ladders and bridges, so the term "Jingkieng Jiri" (alternate spelling:

"Jingkieng Jri") is used for both kinds of architecture.

Interestingly, though I've not stumbled into as many living root ladders

as I have living root bridges, I have come across two very distinct

methods for modifying Banyan tree roots into structures one can climb up

and down. The first is simply to train roots horizontally so that they

form rungs. The second is to cut out rungs into large, already

established Banyan tree roots. The cuts will, over time, expand with the

growing root.

Again, as with living root platforms, not many living root ladders have

been found. There may be many more in southern Meghalaya but their

locations are as yet unknown.

PONGTUNG DOUBLE LIVING ROOT LADDER:

This is the most spectacular example of a living root ladder that I can

across during my month long hike in Meghalaya. It's near the medium

sized Khasi Village of Pongtung, about 20 minutes hiking to the east of

N.H. 40 (one way). After the initial turn off of N.H. 40, reaching it is

fairly straight forward, however you'd need to have a pretty

knowledgeable guide to recognize the turn to begin with. Basically, just

south of Pongtung, there is a concrete barrier on the eastern side of

the road, and the trail begins on the southern side of this. Still, for

now, getting a guide would be the best idea. I'm not sure whether or not

the ladder has seen other visitors. My guides to the bridge were from

Burma Village, and weren't really acquainted with the tourism scene.

The structure is exceptional because it consists of two distinct living

root ladders, one above the other, which employ two separate modes of

living root construction, though both ladders are formed from a single

tree. The path where the ladder was formed had to head down a cliff, so

the original planters decided to create the ladder where there were a

couple of tall natural steps in the cliff face. The ladder was sort of

draped over these steps. Unfortunately, this arrangement means that,

from the upper ladder, one can't see the lower, and vise versa, so

getting a really satisfying photo of the structure in its entirety

wasn't an option when I visited.

The shorter upper ladder uses a method whereby a number of roots were

trained horizontally in order to form a series of very closely set

rungs. On the lower ladder, it begins with the same method, though over

the majority of the structure steps were formed by directly modifying

the roots. It looks as though the makers of the ladder simply took a

machete and carved out a series of gashes in roots that had already

established themselves and the gashes then expanded along with the

roots, creating a series of steps.

Climbing the upper part of the Pongtung living root ladder

This is the lower part of the Pongtung living root ladder. Notice that

at the top, near the kid, are several rungs like those on the upper part

of the ladder. Those oval shaped holes in the sides of the roots are

the steps that have been formed with machetes

Looking straight down to the ground from the top of the lower part of the living root ladder

KONGTHONG LIVING ROOT LADDER:

This living root ladder is located right before the spectacular living root bridge I've named Kongthong 1 in the post The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 3: Bridges of the 12 Villages. Any hike from Kongthong to the living root bridge will mean climbing this ladder.

My friend Roy on his way up the Kongthong living root ladder

Roy ascending. Note the horizontal rung near the bottom of the picture

Looking down from the top of the Kongthong living root ladder

RANTHYLLIANG 8 (HYBRID BRIDGE/LADDER):

Note that more pictures of this bridge are included in the post The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 2: Bridges Near Pynursla

It come as no surprise that many living root structures simply don't fit

neatly into any particular category. For example, Rangthylliang 8 is

both a living root bridge and a living root ladder. You can see in the

photo below that the roots hanging down from the bridge have been used

to form several rungs of a ladder that provides access to the stream the

bridge crosses. A swing was also made out of the roots hanging down

from the bridge, so you could even say that Ranghtylliang 8 serves three

separate purposes at once!

Morningstarr climbing the living root ladder

KUDENG RIM LIVING BLEACHERS:

This was one of my favorite discoveries of my month long trek. In the

village of Kudeng Rim, next to their football field, a Banyan Tree has

been modified to serve as living root root bleachers. It seems to have

been altered specifically for the purpose of allowing the villagers to

watch football games from a lofty vantage point.

The tree has been altered in two ways. First, roots have been trained so

that, rather than hanging down onto the ground, they run closely around

the outside of the tree, which makes it easier to climb up into.

Secondly, several living root platforms have been created in the

branches of the tree by interweaving aerial roots.

This is an example of a piece of living root architecture where I really

am surprised that no one's ever posted anything about it online. Unlike

many of the obscure living root bridges, it's not at all hard to get

to, given that it's right next to Kudeng Rim. I would even go so far as

to say that, if you knew where it was, it would be vastly easier to

access than, for example, the world famous living root bridges of

Nongriat.

Yet, somehow, this fascinating structure has up until now remained entirely off the radar.

The Living Root Bleachers are in the tree directly behind the three kids in the center of the photo

Two people from Kudeng Rim in the Living Root Bleachers. Here one gets a

good look at the way the secondary roots have been trained to adhere

directly to the side of the tree. Without them it would be much harder

to climb up into it

Up on one of the platforms. While the roots of the platform are

relatively thin, the fact that there are so many of them makes it safe

to stand on

Another platform, facing a different direction

MYSTERY OBJECT NEAR RANGTHYLLIANG:

I'm not sure I know how to characterize this thing. It's primary purpose

might be to serve as a retaining structure. You can clearly see

something like a walkway made of roots near the bottom of the picture.

However, the archway, and the small but obviously trained root that you

can see running across it, are features that I've never seen in any

other living root structure. Unfortunately, I had to hurry past the

Mystery Object, so I could only get this one very insufficient

photograph

RANGTHYLLIANG REMNANT OR FAILED BRIDGE:

I spotted this from Rangthylliang 9, and later from downstream while

fording the river Rangthylliang 9 crosses. What it is is a very long,

straight, and, by the looks of it, trained, Banyan Tree root, suspended

high up above a river. However, with no railings of any kind it could

never be used as a bridge. I never actually took a photo specifically

of it....what you see here are pictures of other things, where this was

in the background, which I cropped to make this object as clear as

possible.

I was told at the time that this was just a random root. However,

looking at it again, I don't see how that could have happened. I think

there are two possible explanations for what this thing is. First: It

might be a remnant of a much larger living root bridge that got mostly

swept away. Second: It might be a bridge that failed to form properly

and was abandoned.

The unknown object is that black line near the bottom of this

photograph. It's hard to imagine that this root fell out like that

naturally

A highly zoomed in photo looking at the same object. Unfortunately, I

didn't have the time to see where the root began and ended. However, one

thing that can be said on the basis of this picture is that the root

has been there for a very long time, judging by its thickness

RANGTHYLLIANG DOUBTFUL BRIDGE:

As you might suspect, when it comes to living root architecture there

are some cases where its not entirely clear weather the structure in

question is natural or man made. The Doubtful Bridge of Rangthylliang is

such an example. More or less, it's just one big root across a ravine.

It is, however, a useful root, which a guy from Rangthylliang does use

to cross the ravine in the monsoon season, though with a bamboo pole

attached to provide a railing.

In fairness, I am told that said root was planted, though I've also seen

plenty of similar things that had formed naturally, so I'm just not

sure.

Morningstarr looking up at the Doubtful Bridge of Rangthylliang

Another look at the Doubtful Bridge of Rangthylliang

RYMMAI REMNANT BRIDGE:

This is a small section of a largely destroyed bridge near the village

of Rymmai. The original bridge would have been a double span structure,

with the two parts of bridge leading both to and from a small island in

the middle of a fairly wide stream. The longer part of the bridge,

which would have crossed the stream's main channel, is gone, though a

small part that crosses the narrower part of the stream survives.

The ex-headman of Mawshuit village standing on the remnant of the living root bridge at Rymmai

RUINED BRIDGE AT KUDENG RIM:

There are many places in the Khasi and Jaintia Hills where one can see

the sites of living root bridges that have been recently destroyed. This

is an example near the village of Kudeng Rim. The bridge was apparently

destroyed in a fire. One threat to the survival of living root

structures is the fact that the actual rubber in Banyan trees is highly

flammable. I was told that this particular bridge was destroyed a few

years back when someone failed to put out their bidi before throwing it

away as they crossed the bridge. Once a fire really gets going in the

roots of a Banyan Tree, particularly in the dry season, it's virtually

impossible to put out. The roots may as well be permeated with rubber

cement.

The site of the destroyed bridge near Kudeng Rim. You can see remnants

of the structure on either side of the stream. Also, note the root

hanging down from above, which looks as though it was once part of the

living root bridge

KHONGLAH REINCARNATE BRIDGE:

I'm using the term "Reincarnate Bridge" to denote instances where living

root bridges have been destroyed, and then other bridges (usually made

from bamboo) have been put up in exactly the same place. Frequently,

these are hybrid structures, where the remnants of the destroyed bridges

are incorporated into the new constructions.

The Khonglah Reincarnate Bridge. It's a steep bouldering expedition

downstream from the bridge I called Khonglah 6 in the first post in this

series. Here, you can see the tree that the former living root bridge

was made from

SHNONGPDEI REINCARNATE BRIDGE:

This is another example where a bamboo bridge has been built at the site

of a destroyed living root bridge. This is upstream from the bridge I

referred to as Shnongpdei 1.

The original living root bridge in this case was fairly close to the

water. Since flash floods in the area have gotten worse of late due to

changing agricultural practices, the builders of the new bridge have

deliberately raised the newly constructed bridge high off the stream.

Rothell Kongsit at the Shnongpdei Reincarnate

Another view on the Shnongpdei Reincarnate. At the time, it was

impossible to walk out on this bridge. The bamboo had not been changed,

and was partially rotted out...a problem one does not have with living

root architecture...

NONGPRIANG REINCARNATE:

At one time, this must have been a truly spectacular living root bridge.

In this case, a part of the original living root bridge survives, and

has been combined with the bamboo bridge. Secondary roots are growing

along the length of the newly built structure, and appear to be being

encouraged to do so. Perhaps, some time in the future, roots from either

side of the bridge will be linked together, and a new living root

bridge will be formed. Of course, what destroyed the bridge originally

will remain a factor, though were the area to become a tourist

attraction, the people of Nongpriang might decide to regrow and protect

the bridge for that reason.

The Nongpriang Reincarnate. The tree that the bridge is formed from is

huge, suggesting that there might have been a bridge here for a very

long time. The living root bridge might have gone through several

iterations before the one that was most recently destroyed

Here you can see the place where remnants of the destroyed living root

bridge and the newly built bridge meet. Note the way that chords of

young roots are being encouraged to grow out along the span. While this

may not be a full living root bridge again any time soon, the young

roots may well get worked into the existing framework to strengthen it.

This raises the question of how often living root bridges, rather than

being planted and begun as root bridges, are instead formed by growing

out roots on conventional structures. There is, for example, a hybrid

steel-wire structure near the village of Nongriat where such a method is

being employed to form a new living root bridge

Looking out along the span of the Nongpriang Reincarnate showing how far

along the bridge the young rubber tree roots have reached

So, that, finally, ends my posts on the living root architecture I

reached on my month long hike from Shnongpdeng to Cherrapunji earlier in

2015. While I discovered vastly more than I was expecting to, the truth

is the biggest discovery was that, as much as I found, such evidence as

there is points to there being vastly more living root architecture in

the region. There is so much more work to be done, and all I've put down

here was nothing more than a reconnaissance.

The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 3: Bridges of the 12 Villages

My friend Roy on a spectacular, never before visited living root bridge

near the village of Kongthong, in the heart of a region called the

Katarshnong, or 12 villages

First off, for more information on obscure living root bridges, go to: The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 1, covering the living root bridges of the Dawki region, and The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 2,

which covers the area with the highest (known) density of living root

architecture, the hills and valleys surrounding the small town of

Pynursla.

Before getting into this post I would just like to thank Rothell Kongsit

and all the folks in Kongthong village who showed me around the

Katarshnong. Needless to say, my reaching what you see below never would

have been possible without them!

So, moving right along...

THE TWELVE VILLAGES (Known locally as the "Katarshnong")

VILLAGES COVERED: KONGTHONG-SHNONGPDEI-MAWSHUIT-NONGSHKEN-SOHKYNDUH-NONGPRIANG

The name 12 Villages, or Katarshnong, refers to a rugged region of

slopes and valleys which is between two of the great ridges of the Khasi

Hills. Were one to draw a straight line from Pynursla to Sohra, it

would pass over the Katarshnong, and would be only, maybe, seven or

eight miles miles in length. But crossing the same area on foot, as I

found out earlier this year, is far less straightforward, and involves

going up and down endless ridges and valleys, through some of the most

isolated settlements in the region.

The area is not, as yet, famous for its living root architecture. As far

as I can tell most of the living root bridges in the region have not

been visited by outsiders, and even people in the area engaged in

promoting tourism have not regarded the Katarshnong's living root

bridges as an asset when it comes to attracting visitors (though that

might have changed somewhat after my visit).

As it is, what has attracted a (very tiny) trickle of visitors to the

area is a unique cultural practice called "Jingrwai Iawbei," where at

birth the children of certain villages are given a sort of musical name,

or theme, by their grandmothers. The people of this regions use this

musical nomenclature to communicate to each over long distances. For

example, if two people are working out in the their fields, separated

by, let's say, a valley, instead of calling out to each other by name,

they'll actually sing out each other's songs.

For good reason, it is this custom which the area is becoming known for (though it is still exceedingly remote), but the region also has a number of spectacular, and largely unvisited, living root structures. As for how many exist in the Katarshnong, it's hard to say. My travels merely took me on a fairly shallow reconnaissance of the region, rather than giving me the chance to do a proper survey. I do know that, at one time not too long ago, there were many more living root bridges in the Katarshnong. Unfortunately large numbers have succumbed of late to fires and landslides. Of all the areas I covered on my long hike, it seemed like it was this area where the living root structures were in the greatest danger. Vast swathes of the region's jungle are very rapidly being burnt down and replaced with a variety of grass used for making brooms, and this process is destroying most of the area's living root bridges. It's hard to imagine that there will be many left in a decade or so, unless tourism in Kongthong takes off fairly soon, and the people of the region realize just how much they have to gain from preserving their heritage (and what little remains of their jungle).

Of all the living root bridges on this page, the only one which seems to have been visited before I reached it is MAWSHUIT 1. Otherwise, the photos of the living root bridges you see here are the first ever to appear online.

KONGTHONG: 2 BRIDGES, OTHERS LIKELY

At the moment, Kongthong is the most tourist friendly village in the Katarshnong region. It even has overnight facilities in the form of the newly built "Kongthong Travelers Nest." It is probable that in the next few years Kongthong will become a village tourism destination to rival Nongriat, though its not quite there yet. It makes an excellent base for exploring the center of the Katarshnong, and also affords some of the best views I've seen in Meghalaya, where one can look out over a huge expanse of the surrounding hills and valleys, all the way out to Pynursla.

It also happens to be the most accessible place to experience "Jingrwai Iawbei." While there are several other villages where the phenomenon seems to occur, none of them have significant tourist facilities.

KONGTHONG 1:

This is one of the most distinctive of all living root bridges, and also one of my personal favorites. The way it's main span slopes upwards makes it look almost like a living root ladder, and in all my time in Meghalaya, I've not seen another living root bridge like it.

I was told that I was the first outsider to come to Kongthong 1. That being said, after making it all the way to Kongthong, reaching this bridge is not all that difficult: There is a very clear path that starts right next to the village, and heads almost straight down to the living root bridge, crossing an exceptionally long steel wire suspension bridge on the way. By the standards of the Khasi Hills, the path is almost gentle. However, when I first went my guide Roy took me up to the living root bridge through the bed of the river Umrew. This route takes one through spectacular canyon scenery, and is also highly recommended, though it's a longer and more strenuous hike/canyon scramble.

Before you reach Kongthong 1, there is a living root ladder, which I'll talk about in my last post in this series.

For good reason, it is this custom which the area is becoming known for (though it is still exceedingly remote), but the region also has a number of spectacular, and largely unvisited, living root structures. As for how many exist in the Katarshnong, it's hard to say. My travels merely took me on a fairly shallow reconnaissance of the region, rather than giving me the chance to do a proper survey. I do know that, at one time not too long ago, there were many more living root bridges in the Katarshnong. Unfortunately large numbers have succumbed of late to fires and landslides. Of all the areas I covered on my long hike, it seemed like it was this area where the living root structures were in the greatest danger. Vast swathes of the region's jungle are very rapidly being burnt down and replaced with a variety of grass used for making brooms, and this process is destroying most of the area's living root bridges. It's hard to imagine that there will be many left in a decade or so, unless tourism in Kongthong takes off fairly soon, and the people of the region realize just how much they have to gain from preserving their heritage (and what little remains of their jungle).

Of all the living root bridges on this page, the only one which seems to have been visited before I reached it is MAWSHUIT 1. Otherwise, the photos of the living root bridges you see here are the first ever to appear online.

KONGTHONG: 2 BRIDGES, OTHERS LIKELY

At the moment, Kongthong is the most tourist friendly village in the Katarshnong region. It even has overnight facilities in the form of the newly built "Kongthong Travelers Nest." It is probable that in the next few years Kongthong will become a village tourism destination to rival Nongriat, though its not quite there yet. It makes an excellent base for exploring the center of the Katarshnong, and also affords some of the best views I've seen in Meghalaya, where one can look out over a huge expanse of the surrounding hills and valleys, all the way out to Pynursla.

It also happens to be the most accessible place to experience "Jingrwai Iawbei." While there are several other villages where the phenomenon seems to occur, none of them have significant tourist facilities.

KONGTHONG 1:

This is one of the most distinctive of all living root bridges, and also one of my personal favorites. The way it's main span slopes upwards makes it look almost like a living root ladder, and in all my time in Meghalaya, I've not seen another living root bridge like it.

I was told that I was the first outsider to come to Kongthong 1. That being said, after making it all the way to Kongthong, reaching this bridge is not all that difficult: There is a very clear path that starts right next to the village, and heads almost straight down to the living root bridge, crossing an exceptionally long steel wire suspension bridge on the way. By the standards of the Khasi Hills, the path is almost gentle. However, when I first went my guide Roy took me up to the living root bridge through the bed of the river Umrew. This route takes one through spectacular canyon scenery, and is also highly recommended, though it's a longer and more strenuous hike/canyon scramble.

Before you reach Kongthong 1, there is a living root ladder, which I'll talk about in my last post in this series.

Roy stands mightily upon Kongthong 1. How the original tree wound up in

this strange configuration is hard to say. The natural center of the

tree seems as though it's being held up by deliberately trained living

root load bearing members that appear younger than the branches of the

tree above

This is the view of Kongthong 1 from upstream. It can also be viewed as a

dual span living root bridge; The first span is the ramp-like structure

you see here, while the second is a short, though clearly deliberately

trained, span which leads from the center of the tree back to the

opposite bank

KONGTHONG 2:

This is a small, apparently damaged, living root bridge, about 40 meters

upstream from Kongthong 1. An attempt is being made to grow new roots

onto it to make it functional again.

Kongthong 2

SHNONGPDEI: 1 BRIDGE

Not to be confused with Shnongpdeng, Shnongpdei is an exceedingly remote

village, about a ninety minute hike north of Kongthong. You're only

real chance of reaching it would be to contact the tourist society in

Kongthong and have them guide you.

The upper reaches of the river Umrew flow next to Shnongpdei, and the

one (known) living root bridge in the area is accessed by climbing down

from Shnongpdei into the river, and then scrambling some distance down

the watercourse to the living root bridge. There may be an easier way to

get to the bridge, though no matter what, reaching it would entail a

certain amount of scrambling.

Both from physical evidence and what I was told at the time, the river

next to Shnongpdei was once spanned by quite a few living root bridges,

though these have mostly been been destroyed in recent years due to

rising flood levels, again, a result of the conversion of the jungle

into broom grass fields. Several have, however, had a reincarnation of

sorts in the form of bamboo bridges (I'll also cover one of these in my

last post). The one living root bridge that has survived has only been

able to because it's partially protected from monsoonal floods by a big

boulder.

The protection offered by the boulder, however, didn't prevent the

bridge from being knocked down sometime in the past. Most of the bridge

was destroyed at one point, leaving only part of it standing on the

western bank. Then the bridge was then reconnected, I'm told, maybe 60

or 70 years ago (figures are fuzzy under such circumstances.)

The living root bridge was originally planted to service a village

which no longer exists, and the paths down to the structure seem to have

largely disappeared. The locals therefore didn't see any real reason to

maintain the bridge, and at the time I visited, parts of it had fallen

apart.

I was led down to the living root bridge by the head of Kongthong's

tourism society, Rothell Kongsit, a couple of other folks from

Kongthong, and also some people from Shnongpdei. It was Rothell's first

visit as well. When we arrived at the bridge, Rothell explained to

everybody that the bridge could be a major tourism asset, and that they

shouldn't let the structure be destroyed. All the locals then started on

the spot repairs on the living root bridge. Therefore, the living root

bridge I left behind was very different from the one I first

encountered. This marked the only time where I witnessed a living root

bridge actually being constructed.

I do hope the bridge survived this year's monsoon season. There is a

fairly good chance that, as I write this, the bridge has already

disappeared.

Shnongpdei 1, classic, simple, and spectacular. It is a fairly long

bridge (I would estimate that it is slightly longer than the longest

living root bridge in the Nongriat area). It looks much smaller from

upstream than it does from downstream, because the boulder in the

background obscures much of it. Rothell is second from left

The view across the span, from the eastern side of the living root

bridge, before any repairs had been done. You can see here that the

railings on the left side the picture are less intact than those on the

right

In the process of repairing the bridge, using the rubber tree roots

available. Notice the thin roots coming in from the right side of the

frame. This is a sort of a living root variation of a feature one sees

frequently on modern steel wire bridges. Once those roots strengthen,

they'll serve to keep the bridge from swaying too much in the wind and

in flood waters. I'm not sure if it'll work or not: The roots probably

won't have grown strong enough by the time the bridge is put to the test

More repairs being done. Note the number of roots that were hanging down

that have been incorporated into the structure. If they survive this

year, they'll add greatly to the stability of the living root bridge.

There always seems to be a certain amount of opportunism that goes into

creating and maintaining these structures

The newly repaired railing. These roots will take a couple of years to become useful

The whole team at work on Shnongpdei 1

MAWSHUIT: 1 BRIDGE, 3 OTHERS KNOWN TO EXIST BUT NOT VISITED

Mawshuit is a small village west of Kongthong. It has also seen a few

visitors. The village, and the root bridge listed here, would be

accessible in a day hike from Kongthong, though I stayed the night in

Mawshuit. There seem to be quite a few living root bridges in the near

vicinity, and I am told that there are many more in the surrounding

villages, though at the time I could only manage to visit one. Exploring

this region more thoroughly will be a high priority when I return.

MAWSHUIT 1:

This is a spectacular, though sadly dangerous and badly maintained,

living root bridge on the Muor River, northwest of Mawshuit. It is, to

my knowledge, the only living root bridge in this post which has been

visited, photographed, and had information about it published online. A

tour outfit called Vagabond Expeditions reached it sometime this year,

though their blog post about it is dated several months after I visited.

Also, a few trekking groups, including one apparently made up of

American college students, have stayed in Mawshuit and trekked to the

bridge. However, visitors are still extremely rare, and, if anything,

seem to have ceased entirely, at least of late.

The bridge itself, at least according to the Vagabond Expeditions

website, used to service a major trail that connected Mawshuit with the

nearby small town of Khrang, though the entire trail was mostly

abandoned around 1996 after an alternate route was constructed.

The bridge is clearly a very young one: So much so that the roots are

thin enough that in places you could slip right through them. The bridge

is also very high up above its stream. These two factors combine to

make the living root bridge one of the most dangerous I've ever

encountered. I learned this the hard way when I wandered right out onto

the middle of it and then realized I was centimeters from doom...I'm

afraid, unless you're tiny, going out on it is probably not a good

idea.

It is, however, in one of the most spectacular settings of any living

root bridge, as it spans a narrow, rocky, gorge. Were the people of

Mawshuit to put their minds to it, they could develop and maintain the

bridge. If the bridge itself were not in such poor condition, the view

of it from downstream could become one of Meghalaya's great post card

shots, and the village could do a steady business in bringing people to

see it (a guide, at least at this stage, would be a must).

The former headman of Mawshuit village, standing upon Mawshuit 1. He is,

of course, much smaller than I am, making the bridge much less of a

safety hazard for him. You'll notice that there's a steel wire bridge

right above it. I'm not sure which came first. Both are abandoned and

rather too dangerous to cross.

The tangled view of the bridge from the eastern end of it. This is what

you see first when you approach the bridge from Mawshuit. It really

isn't very picturesque from this vantage point. Here you get a good

impression of how thin the roots are

Closer to the center of the bridge

Zooming in on the span and the ex-headman

NONGSHKEN: 1 BRIDGE

Nongshken is a tiny village on the long route between Mawshuit and

Cherrapunji. If you were to walk from Cherrapunji to Kongthong, you

might come this way. I have absolutely no information on other living

root bridges in the area.

NONGSHKEN 1:

This is a pretty, classic, medium length living root bridge in a small

wooded valley below Nongshken. It lies directly on the fairly important

route linking the villages of Rymmai, Nongshken, and Sohkynduh.

Nongshken 1

The view from upstream....

....and from downstream. The man in the photo was my guide from the village of Rymmai

SOHKYNDUH: 1 BRIDGE

Sohkynduh is a village within sight of Cherrapunji, and would be

accessible from Cherrapunji itself in about a five hour (at a moderate

pace) trek. The village does not have any tourist facilities, and is at

this point very unused to outsiders. However, if it did have a home

stay, it would make a very good base to begin exploring the Katarshnong

from.

I only spent one night there, though that was just long enough to see

that the village is the terminus of a network of trails that lead into

the southern part of the Katarshnong, a region in which I have never set

foot, though which almost certainly has a significant number of

examples of living root architecture.

SOHKYNDUH 1:

This is a small but very interesting, and clearly very ancient, living

root bridge a steep two and a half hour hike (both ways) from Sohkynduh.

It has a very distinctive, triangular, profile, as the planters decided

to use what would become some of the tree's main branches in the

structure of the living root bridge.

Sohkynduh 1

My guide from Sohkynduh on the living root bridge

A local villager crossing Sohkynduh 1. Note how thick the root next to

him is. Allowing for the fact that the man is probably very short, the

root must still be in the vicinity of two and half to three feet thick,

meaning the bridge must be hundreds of years old

NONGPRIANG: 1 BRIDGE, SEVERAL DESTROYED BRIDGES

Walking from Kongthong, Nongpriang is the last village one goes through

before reaching Cherrapunji. It lies directly at the bottom of the steep

slope to the east of Cherrapunji, I'd say about an hour's walk

downhill, or a three hour's walk up.

It still manages to be a pretty little village, though the surroundings

are sad: As I walked through, the jungle in the area was literally in

the process of being burnt down. It's clear that, not too long ago,

there were a great many living root bridge around this village. While I

saw one functional one, I also saw two other places where living root

bridges had been, though they were destroyed recently. I didn't have the

time to do a proper survey of the area, so it's more than possible that

there are other, still functional, living root bridges accessible from

Nongpriang.

NONGPRIANG 1:

This is a small bridge on the path between Sohkynduh and Nongpriang.

It's very near some large patches of jungle that were cleared in

shifting cultivation fires recently. It looked to me at the time that

the bridge itself had only narrowly missed being consumed in the fire.

It also happens to be the last living root bridge I discovered on my

month long trek. A few hours after the photos below were taken, I was

back in Cherrapunji.

My guide on Nongpriang 1

Nongpriang 1

The view of Nongpriang 1 from upstream

Coming soon, the final entry in this series: The Undiscovered Living

Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 4: Living Root Ladders and other uses for

Living Root Architecture

The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 2: Bridges Near Pynursla

Jungle Man John Cena and friend cling to roots with the longest known living root bridge in the background

First, for more info on obscure living root bridges, go to: The Undiscovered Living Root Bridges of Meghalaya Part 1: Bridges of the Umngot River basin

Before I get into the post, I'd just like to thank my friend Alan West,

who pointed me in the general direction of the area in this post, and

also my redoubtable jungle guides: Morningstarr, John Cena (A.K.A.

Jungle Man John Cena), and Morningstarr's dad. Without them, I might

very well have seen just a few of the bridges in the area, and then

moved on. These three know their area incredibly well, and were able to

show me places I otherwise would have surely missed. They know that what

they have in their area is something truly of value.

So, moving right along:

PYNURSLA

VILLAGES COVERED: RANGTHYLLIANG / MAWKYRNOT-MYNDRING

Once I had reached the medium sized Khasi town of Pynursla, I had

already vastly exceeded the number of living root bridges that I thought

I could expect to find on my long trek. My assumption was that the

trip's greatest discoveries were probably all behind me. But then

Pynursla blew that notion away. Within a few kilometers of that totally

unassuming, entirely untouristed town, is the highest density of living

root architecture known to exist. In comparison, the living root bridges

around Cherrapunji seem rather thinly spaced out. Even around the

village of Nongriat, at the moment the center of root bridge tourism,

there are only (by my calculations) nine living root structures,

including two rather beyond the tourist zone. In the Pynursla area, I

came across as many on a single hike. Here, I'm listing nineteen structures. There are many more in the area.

Just a warning: The photos below are of very variable quality.

Conditions were often just too rough to have the time to take lots of

really good photos. All nineteen bridges were visited over the course of

only four hikes, and these were all immensely difficult endeavors. My

guides had such a knowledge of the land that they simply did not need

trails. Rather than walking, they often preferred to climb, up and down

unstable slopes, precariously clinging to roots and bushes, me following

as best I could. And, for some of the living root bridges, this was the

best way to reach them. Many living root bridges do not have clear

paths to them (or paths leading to them at all). Those that have

survived yet outlived their usefulness are lost out in the jungle,

forgotten, but still growing stronger.

The incredible density of living root structures in this area should not

lead to the assumption that there is no place in Meghalaya that has

more of them. The only thing that the number of living root bridges

around Pynursla suggests to me is that, in all likelihood, there are

places with just as high, or even higher, concentrations of living root

architecture, that are simply further from civilization and therefore

will take longer to become known (if the bridges aren't destroyed in the

meantime, which is likely).

RANGTHYLLIANG / MAWKYRNOT: 16 BRIDGES (MANY MORE UNVISITED)

At the moment, the village with the most known living root bridges is a

small settlement, almost a kind of suburb, of the town of Pynursla

(though it in fact predates the town), called Rangthylliang. The village

is on the edge of a vast canyon system, and it's land slopes down into

the gorge via a huge, steep, jungle covered ridge. An astonishing number

of living root structures occur on this promontory, a handful of which

are already starting to be famous, though the vast majority are unknown.

While I can reasonably safely say that I was the first foreigner to

reach most of these bridges, several very local Khasi tourism societies

do operate in the area, though so far they seem to have had little luck

promoting the area. Maybe this post will help in a small way.

There are a few bridges that have been "discovered" as it were. These

are what I'm listing as Rangthylliang 1-5. Several of these are among

the most extraordinary known living root bridges, including the world's

longest example, and also an (unfortunately damaged) "Triple Decker."

There is, sadly, something of a political dispute over the world's

longest bridge: It actually crosses over the stream that marks the

border between Rangthylliang's land and that of a village called

Mawkyrnot. The bridge appears to have been planted on the Rangthylliang

side of the border, but it's easier to access from Mawkyrnot. The only

tourism that the area is seeing at the moment is a little bit coming

from the world famous village of Mawlynnong, and a few guides from that

village take tourists to the longest bridge via Mawkynot. The bridge

seems to be claimed by that village, which is something that's not going

to sit too well in Rangthylliang once the area starts getting famous

and tourist rupees start pouring in...I was told that, back in the hazy

past, the two villages fought wars over that particular piece of

real-estate, so I hope that doesn't start up again.

I'm listing the first five bridge under Rangthylliang, though be advised

that more people in Meghalaya (though not many!) are going to have

heard of Mawkyrnot as the village to approach these bridges from. After

1-5, the rest of the bridges mostly seem not to have been photographed

or visited by outsiders....not that anything on this list has seen more

than a handful of visitors at this point...

RANGTHYLLIANG 1:

This is, in terms of a single span, the longest known bridge (there is

another bridge, later in this post, which might be longer in terms of

its full structural length, through it's divided into two spans). This

is also the most famous bridge on this list, having appeared in a photo

in The Atlantic. The photographer had visited Mawlynnong, and was

brought here. Still, visitors are exceedingly few, though that's likely

to change very soon.

The classic shot of Rangthylliang 1, undoubtedly one of the most

spectacular examples of living root architecture. At over 50 meters,

it's much longer than the longest (known) living root bridge in the

Cherrapunji area. It's also over 30 meters above its stream. The claim

has been made that it is a newly planted bridge, since it does not have

functioning rails composed of living roots. I find this doubtful: The

main root of the structure is very thick, while the tree, which you can

see on the right of this picture, certainly looks like it was modified a

very long time ago. Also, some of the secondary roots coming down from

the main root look to be as thick as small trees. It seems either that

the rails were destroyed at some point, or that the bridge has always

had the current, hybrid, arrangement, where bamboo is used to provide

the actual walkway and hand-railings

Looking up at Rangthylliang 1 from below. Note the way that the tree the

living root bridge is formed of seems to lean out over the precipice.

This would seem to indicate that the tree has been there a very long

time, and that the ground beneath it has been undercut. That also leads

me to believe that Rangthylliang 1 is an older bridge

RANGTHYLLIANG 2:

Rangthylliang 1, 2, and 3, are all within sight of each other.

Rangthylliang 1 and 3 cross the small stream that separates the land of

Rangthylliang and Mawkyrnot. Rangthylliang 2 spans a small brook that

comes down a rocky cliff face and then feeds into the larger stream,

between the other two bridges. It's a very pretty bridge in its own

right, though not an especially photogenic one.

Rangthylliang 2, viewed from a distance

Crossing Rangthylliang 2

RANGTHYLLIANG 3:

This is quite a large, "classic," living root bridge, perhaps 150 meters upstream from Rangthylliang 1.

Jungle Man John Cena swinging on a root, under Rangthylliang 3

Rangthylliang 3

RANGTHYLLIANG 4:

This is a very small bridge between the three pictured above and the

next entry. As I had to keep up with my guides, I only manged to take

one photo, which was out of focus, and wouldn't look like anything if I

posted it here. I would estimate it's about eight feet long.

RANGTHYLLIANG 5 (RANGTHYLLIANG TRIPLE DECKER):

This extraordinary bridge is about a twenty minute (at a reasonable

pace) walk from Rangthylliang 1. When I first visited, I had thought

that it was a "Double Decker," with a similar arrangement to the world

famous Double Decker living root bridge in Nongriat. While perhaps not

quite so perfect as the more famous structure, the Rangthylliang bridge

struck me at the time as rather more spectacular, simply because the

upper span was longer, and also higher above its stream, than the

Nongriat Bridge.

Sadly, the bridge has been damaged very recently. A tree has fallen over

onto the lower span, and if you weren't paying close attention, you

might not even realize that the bridge was a multiple span structure.

That being said, the span that was hit does not seem to have been badly

damaged, it's just partially hidden under a big tree. If there was

somebody in the area who was sufficiently motivated (and there does not

seem to be at the moment), they could probably repair the living root

bridge.

However, just in the last couple of days, as I was scouring the internet

to see if there was any other information on the bridges in this area, I

found something that makes this bridge even more exceptional. It may be

the world's only known example of a "Trip Decker" living root bridge. A

very local Khasi hiking club put up a photo of the living root bridge

from two years ago on their Facebook page. This was before the tree

fell, and what the photo shows is actually three spans.

At the time I visited, I didn't see a third span. It might have been

destroyed, or it might have been hidden by the fallen tree. Also, there

is the possibility that the third span is actually an entirely separate

living root bridge, grown from another tree. Still, whether it is a

double or triple decker structure, Rangthylliang 5 illustrates that the

diversity of living root bridges, and of living root architecture in

general, is vastly greater than than the world assumes.

My guides on Rangthylliang 5. You can see here that the upper span is a

great distance above its stream. The lower span is under that tree

Jungle Man John Cena on the uppermost span

Here you can get a fairly good impression of the arrangement of the two

upper spans. It's a fairly similar to layout of the world famous double

decker living root bridge in Nongriat

Investigating the lower (or middle?) span

Jungle Man John Cena on the upper span

RANGTHYLLIANG 6:

This small, simple bridge is beyond Rangthylliang 5. I've never seen another photo of it online.

Jungle Man John Cena on Rangthylliang 6

RANGTHYLLIANG 7:

This living root bridge is interesting simply because it's very newly

planted. It's two or three years old at most, and probably has at least a

decade to go before it becomes operational.

It's important for two reasons: First, it demonstrates that the actual

practice of creating living root bridges is still alive (though clearly

becoming rarer) in the Rangthylliang area. Second, it is the only newly

planted bridge that I've ever encountered outside of a tourist zone. I'm

reasonably sure no other outsider has seen it.

The roots of Rangthylliang 7 are very thin. I suspect that a large

number of living root bridges actually don't make it past this stage and

are destroyed in landslides, fires, and floods

RANGTHYLLIANG 8:

This is another truly remarkable living root structure, though, funnily

enough, when I visited it didn't even occur to me how unusual it was.

Here, a single tree has been ingeniously modified into both a bridge and a ladder.

The main bridge, which would be an impressive example of living root architecture all by itself. Note the root swing.

My friend Morningstarr climbing the living root ladder, which was made

by training the secondary roots hanging down from the bridge into rungs

Jungle Man John Cena swinging again....he never misses a chance...

RANGTHYLLIANG 9:

This is yet another extraordinary living root bridge.

Two things set it apart. The first is that, as I remember it, this

bridge is higher up off its stream than any I've come across. If memory

serves, the stream was something like 100 meters below. Needless to say,

a fatal drop. The living root bridge crosses a deep canyon.

Unfortunately, at least as far as photography is concerned, it's right

in front of a waterfall (dry at the time I visited) and therefore its

almost impossible to capture its great height in a photograph (in the

time I had...we moved on pretty quickly). A picture looking straight

down from the bridge doesn't look like anything.

The second thing that sets it apart is that the bridge is another double

span structure, but in this case, it's two spans are at a ninety degree

angle to one another, an arrangement which I've never seen

elsewhere....this is one I'm really looking forward to getting back to

and taking more pictures of...

Jungle Man John Cena on Rangthylliang 9. Note the very straight object

near the bottom of the photo. My theory is that this is a failed or

abandoned root bridge. I'll talk about it in the last post is this

series.

RANGTHYLLIANG 10:

This was a bridge that my companions and I crossed over very quickly,

right before we started a near vertical, thirty minute downward climb.

Below is the only picture of the bridge that I managed to take. The

bridge is clearly very old, and has been damaged in several places.

Morningstarr on Rangthylliang 10

RANGTHYLLIANG 11:

This is a spectacular, classic, living root bridge. A second root has

been trained across the river right next to it, creating something like

another "Double Decker," though the other root does not constitute a

separate, functional span.

I wasn't able to establish what the purpose of the second root was.

Currently, there does not appear to be any effort being made to use the

second root to form a new span. What it might be is a remnant of an

older span that has been almost totally destroyed in floods, except for

that one root...or it might just be a mistake...

Looking up at Rangthylliang 11

Closer on the main span and the mysterious second root

My companions on the main span of Rangthylliang 11

RANGTHYLLIANG 12:

This is one of a pair of two small, though very old, living root

bridges, well off any major trails. Living root bridges such as these,

which must be very numerous across Meghalaya, would be absolutely

impossible to find without guides who had an extremely intimate

knowledge of the local landscape.

Rangthylliang 12....yes, the photo doesn't look like much, though this is the best one I managed to take

RANGTHYLLIANG 13:

Judging by the secondary roots growing out of the bottom of this living

root bridge, it must be very ancient...perhaps the oldest I reached in

the Rangthylliang area. As I remember, it was no longer in use.

Morningstarr grins like a madman on Rangthylliang 13

Jungle Man John Cena finding another opportunity to swing on roots, in front of Rangthylliang 13

RANGTHYLLIANG 14:

Rangthylliang 14 and 15 are another pair of small but interesting living

root bridges. Again, without really good guides, I never would have

even suspected they were there. They were accessed by climbing up a

stream bed, the paths they once serviced having long since faded away.

Rangthylliang 14 in the foreground, with 15 in the background. Why the

original planters put the two living root bridges so close together is

an interesting (though probably unanswerable) question

RANGTHLLIANG 15:

This is a short distance upstream from Rangthylliang 14.

Looking up at Rangthylliang 15

RANGTHYLLIANG 16:

This living root bridge is a steep, three hour (one way) downhill hike

from Rangthylliang, near the border of Rangthylliang's land with that of

another village called Myndring. The living root bridge itself is a

very satisfying example of living root architecture, while the setting

of the bridge is one of the most beautiful places I've visited in

Meghalaya. The bridge crosses a small, clear stream right in front of

where it issues from a narrow gorge, poring over a very pretty little

waterfall. There is a nice, swimmable, pool in front of the waterfall,

and if you climb up the falls, there is another, even nicer, swimmable

pool at the top, with yet another small waterfall at the end of that pool.

It's a great place to spend a few hours, though since it's quite some

distance from Rangthylliang or Mawkyrnot, and since those villages don't

have any real overnight facilities as yet, this particular spot will

probably not be overrun by tourists for quite some time.

Rangthylliang 16

The stream in front of Rangthylliang 16. A wonderful place for a rest

MYNDRING: 3 BRIDGES (MORE LIKELY)

Myndring is a small Khasi village on a ridge downhill from Pynursla.

While not very far from the town as the crow flies, it is still very

remote, being only accessible on foot via a steep stairway. My

companions and I approached it from rather an odd direction: We started

in Rangthylliang, then climbed down into the valley between

Rangthyllliang and Myndring, and then climbed up into Myndring from the

jungle. I was told in Myndring that I was the first tourist to visit

within living memory, so the living root bridges pictured below had

probably not been seen by an outsider before.

MYNDRING 1:

Myndring 1 is a huge living root bridge that crosses the river that

marks the boundary between Rangthylliang's land and that of Myndring.

The main tree that the bridge is grown out of is on the Myndring side of

the border, so I'm listing it under that village.

I view this living root bridge as the most important single discovery of my month long trek. This is for several reasons:

The first is that it appears to be a very old bridge, yet it is also

over a large river. What this means is that it is an ancient bridge that

has nonetheless withstood the test of time. It might be 300 years old,

and yet has taken 300 years of abuse from 300 Meghalaya monsoon seasons.

While a few living root bridges still exist on larger streams, they

seem to usually be well up off the water, safe from floods. They are

also, as is the case with the longest bridge near Nongriat, or the Great

Bridge of Kudeng Rim, relatively new living root bridges. This

particular example is, very clearly judging by the root thickness,

ancient, yet it is fairly close to its stream, and is probably bombarded

yearly not just by flood waters, but also with the rocks and brushwood

the floods take down the stream with them.

The second reason it's remarkable is that it is another double span

structure, in this case with one span before the other. Unfortunately,

I couldn't get a picture of the second span (something I hope to do

properly when I return), but what you see in the photo below is only 60%

or so of the complete structure.

The third reason why I view this particular living root bridge as so

exceptional is that, by certain measurements, it might actually be the

longest known example. Rangthylliang 1 certainly is the longest in

terms of a single span, however the bridge below may be the longest in

terms of the distance over which a single organism has been modified.

I'm reasonably sure (though, again, I'll need to revisit!) that both

spans of the bridge put together would be longer than Rangthylliang 1 in

its entirety.

Sadly, as I crossed this bridge I saw that some of the roots were dying

of some sort of disease. It is more than likely that the living root

bridge will be swept away in the next few years, particularly if there's

increased slash and burn agriculture upstream. There isn't any

especially pressing practical reason for the locals to maintain the

bridge: While it once serviced a major trail between Rangthylliang and

Myndring, that path seems to have fallen largely into disuse over a

century ago. As far a tourism is concerned, even if there were

facilities in Pynursla or even in Rangthylliang, it's unlikely that your

average hiker would make it this far. I'm really not sure if this

bridge will be there the next time I visit, meaning that there is a

chance that the photos you see below might be the only ones that are